Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning

Guide for Local Governments

February

2017

FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................................................................... IV

I. INTRODUCTION

..........................................................................................................................................1

Purpose of this Guide

............................................................................................................................ 4

Audience

................................................................................................................................................ 5

Presidential Policy Directive 8

................................................................................................................ 7

National Preparedness Goal

.................................................................................................................... 7

II. NATIONAL RECOVERY PREPAREDNESS EFFORTS

..................................................................................7

National Disaster Recovery Framework

.................................................................................................. 8

National Mitigation Framework

............................................................................................................. 9

Recovery Activities are Locally Driven

................................................................................................. 11

III. KEY CONCEPTS FOR RECOVERY PLANNING

...................................................................................... 11

Disaster Recovery Planning Is a Broad, Inclusive Process

..................................................................... 12

Recovery Planning Builds Upon and Is Integrated with Other Community Plans

................................ 14

Recovery Planning is Closely Aligned with Hazard Mitigation

............................................................ 15

Recovery Planning Is Goal Oriented..................................................................................................... 16

Recovery Planning Is Scalable

.............................................................................................................. 17

Recovery Activities Are Comprehensive and Long-Term

...................................................................... 19

Resilience and Sustainability

................................................................................................................ 19

IV. LINKING PRE-DISASTER RESPONSE PLANNING AND PRE-DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING

.... 21

V. LINKING PRE-DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING AND POST-DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING

. 23

VI. PRE-DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING KEY ACTIVITIES

...................................................................27

VII. STEP 1 – FORM A COLLABORATIVE PLANNING TEAM

....................................................................29

VIII. STEP 2 – UNDERSTAND THE SITUATION

.........................................................................................39

IX. STEP 3 – DETERMINE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

................................................................................ 43

X. STEP 4 – PLAN DEVELOPMENT

............................................................................................................... 49

XI. STEP 5 – PLAN PREPARATION, REVIEW, AND APPROVAL................................................................. 61

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page ii

XII. STEP 6 – PLAN IMPLEMENTATION AND MAINTENANCE ...............................................................65

XIII. REFERENCES

.......................................................................................................................................... 69

APPENDIX A: PLANNING PROCESS COMPARISON

................................................................................... 73

APPENDIX B: STATE, TRIBAL, AND FEDERAL SUPPORT

.......................................................................... 75

APPENDIX C: FACTORS FOR A SUCCESSFUL RECOVERY

.........................................................................77

APPENDIX D: A RECOVERY-ENABLING TOOL: THE RECOVERY ORDINANCE

..................................... 81

APPENDIX E: PRE-DISASTER RECOVERY PLAN COMPONENTS

.............................................................. 83

APPENDIX F: RECOVERY CAPABILITY DOCUMENTATION TEMPLATE.................................................. 87

APPENDIX G: LOCAL PRE-DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING KEY ACTIVITIES CHECKLIST

...............89

APPENDIX H: KEY TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

.......................................................................................... 93

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page iii

FIGURES

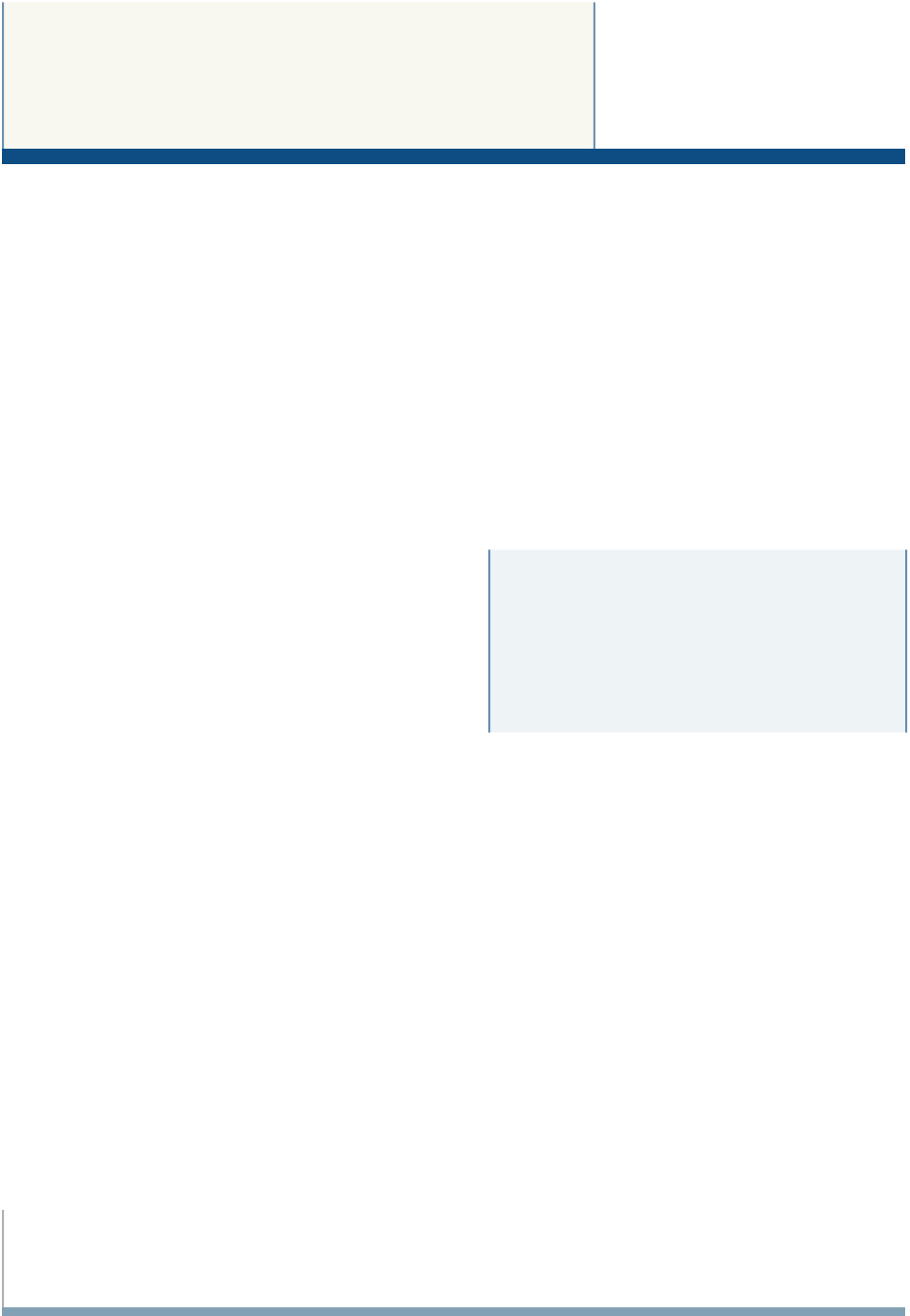

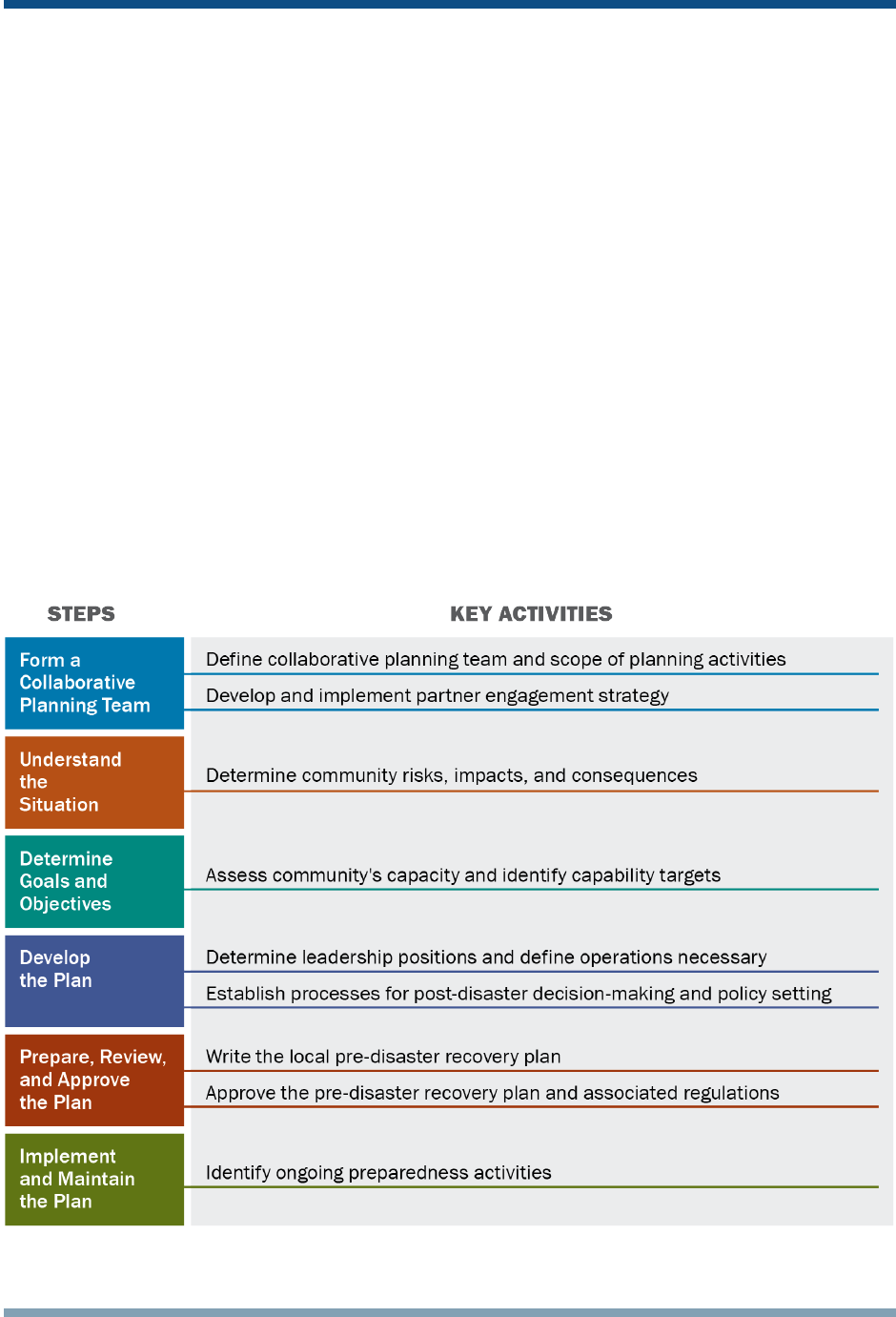

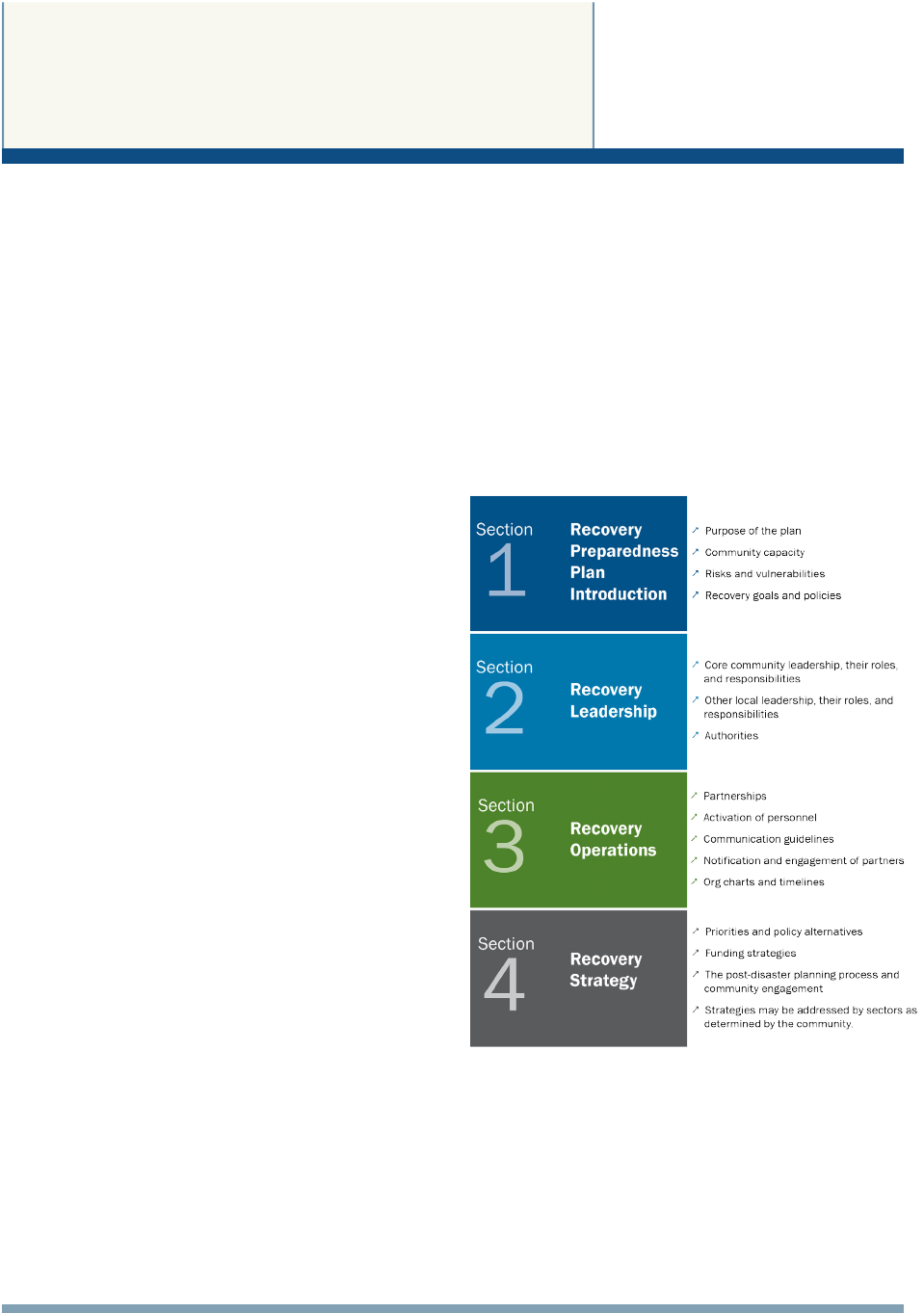

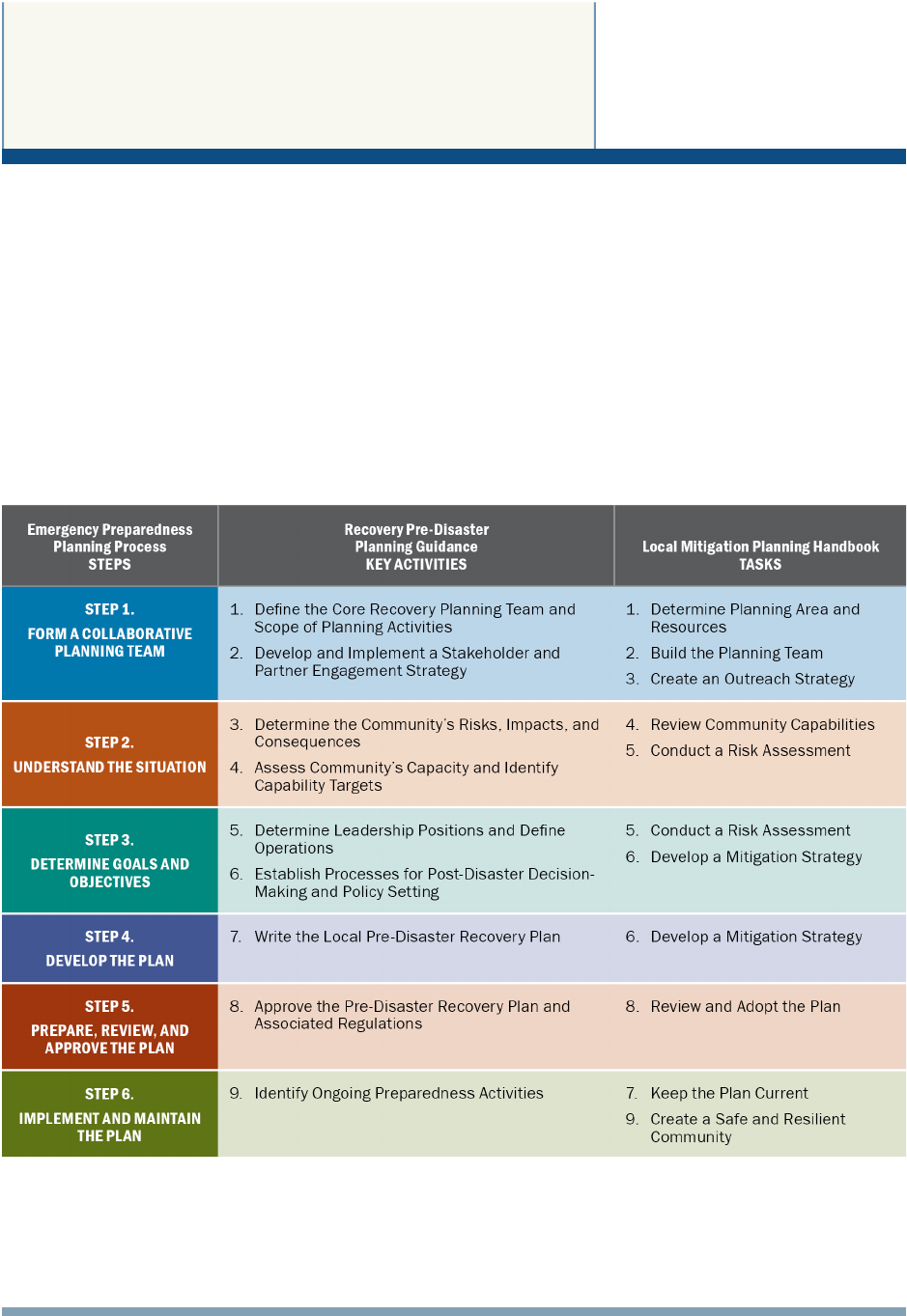

Figure 1 Key Activities in the Pre-disaster Recovery Planning Process ..........................................................4

Figure 2 The Cyclical Nature of Planning ...................................................................................................14

Figure 3 Scalable Recovery System .............................................................................................................. 17

Figure 4 Disaster Response and Recovery Timeline ....................................................................................23

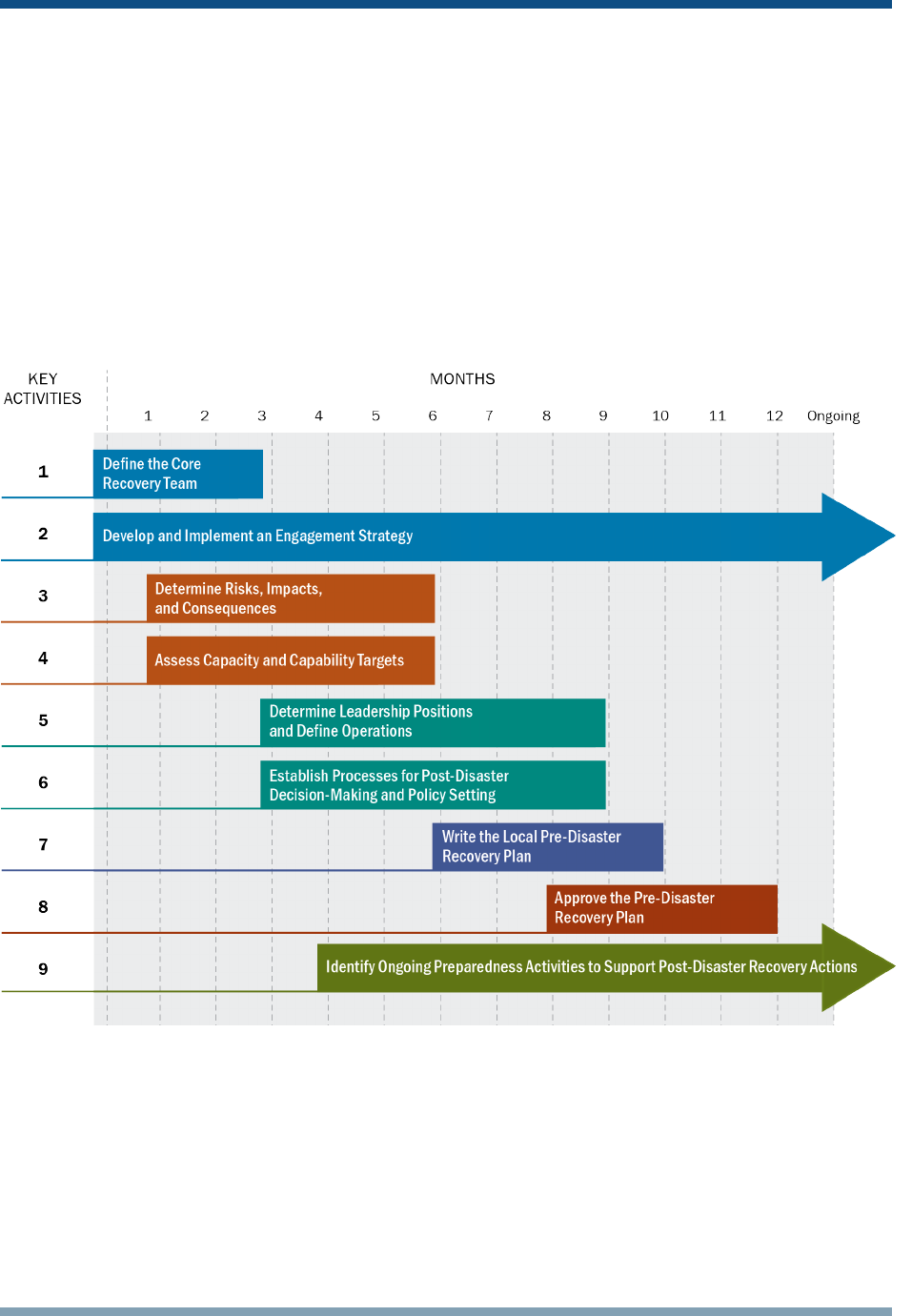

Figure 5 Key Activities in the Pre-disaster Recovery Planning Process ........................................................27

Figure 6 Example Planning Timeline ..........................................................................................................28

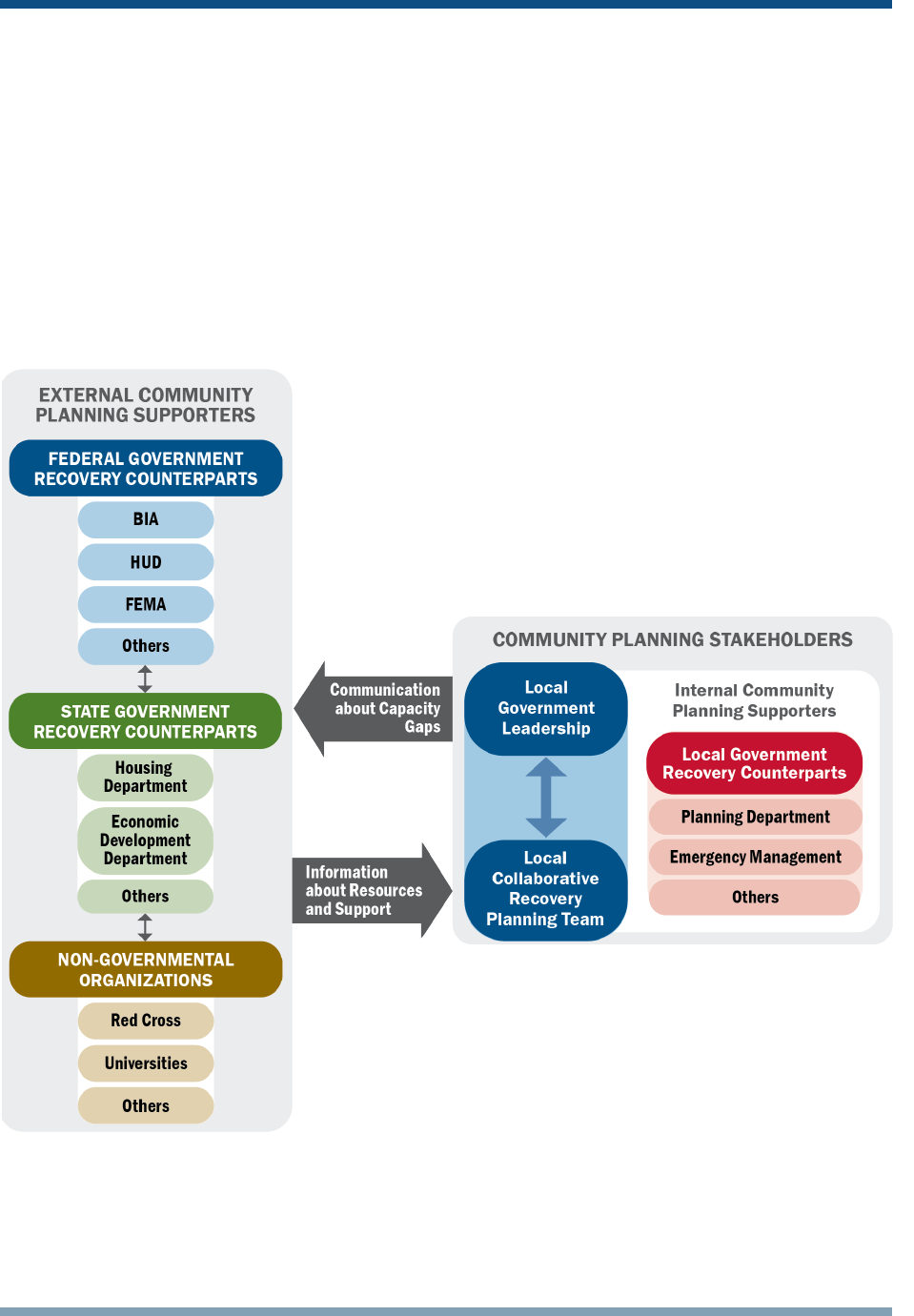

Figure 7 Pre-disaster Planning Communications Map: Community Planning Stakeholders and

External Supporters ......................................................................................................................30

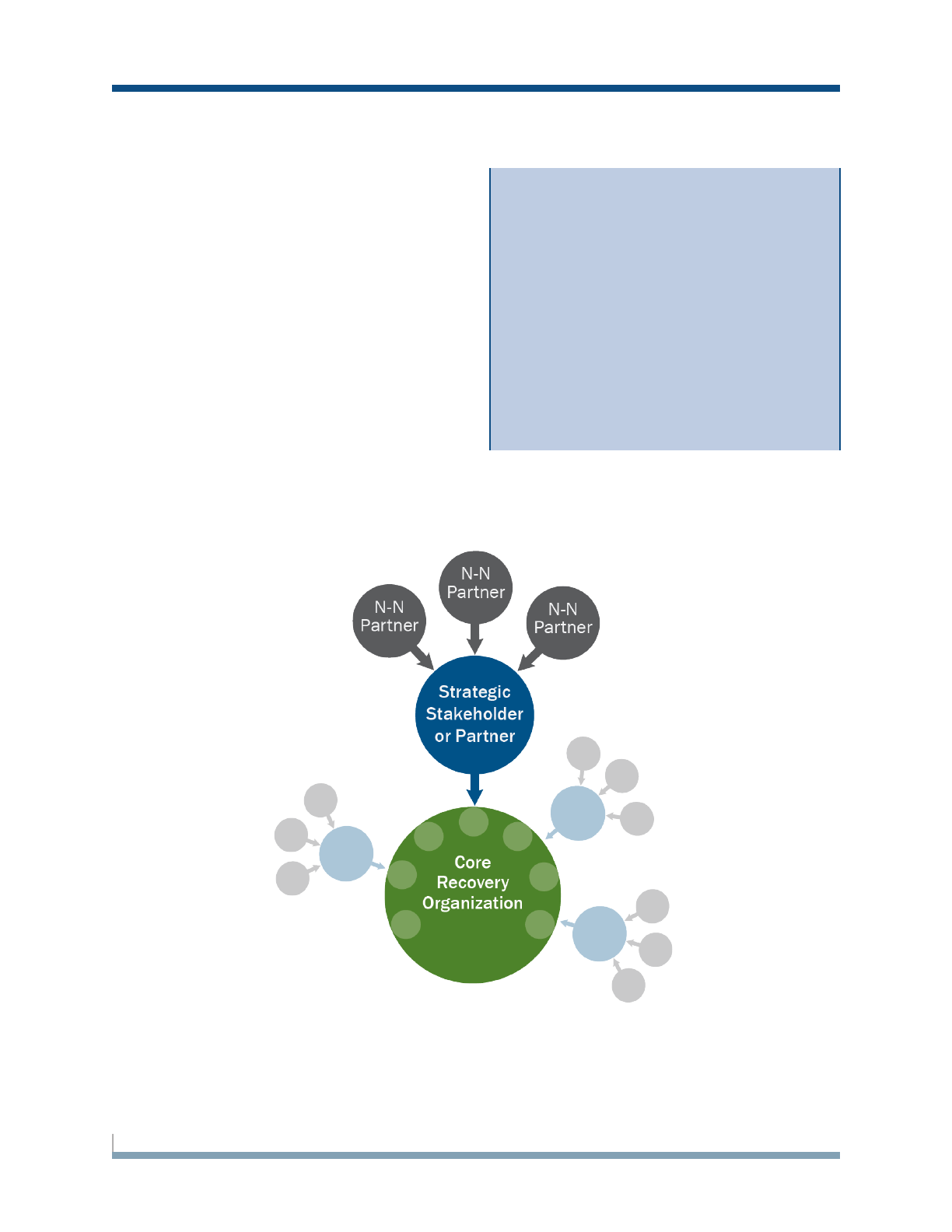

Figure 8 Community and Regional Resilience Institute (CARRI) Network of Networks Concept ...............35

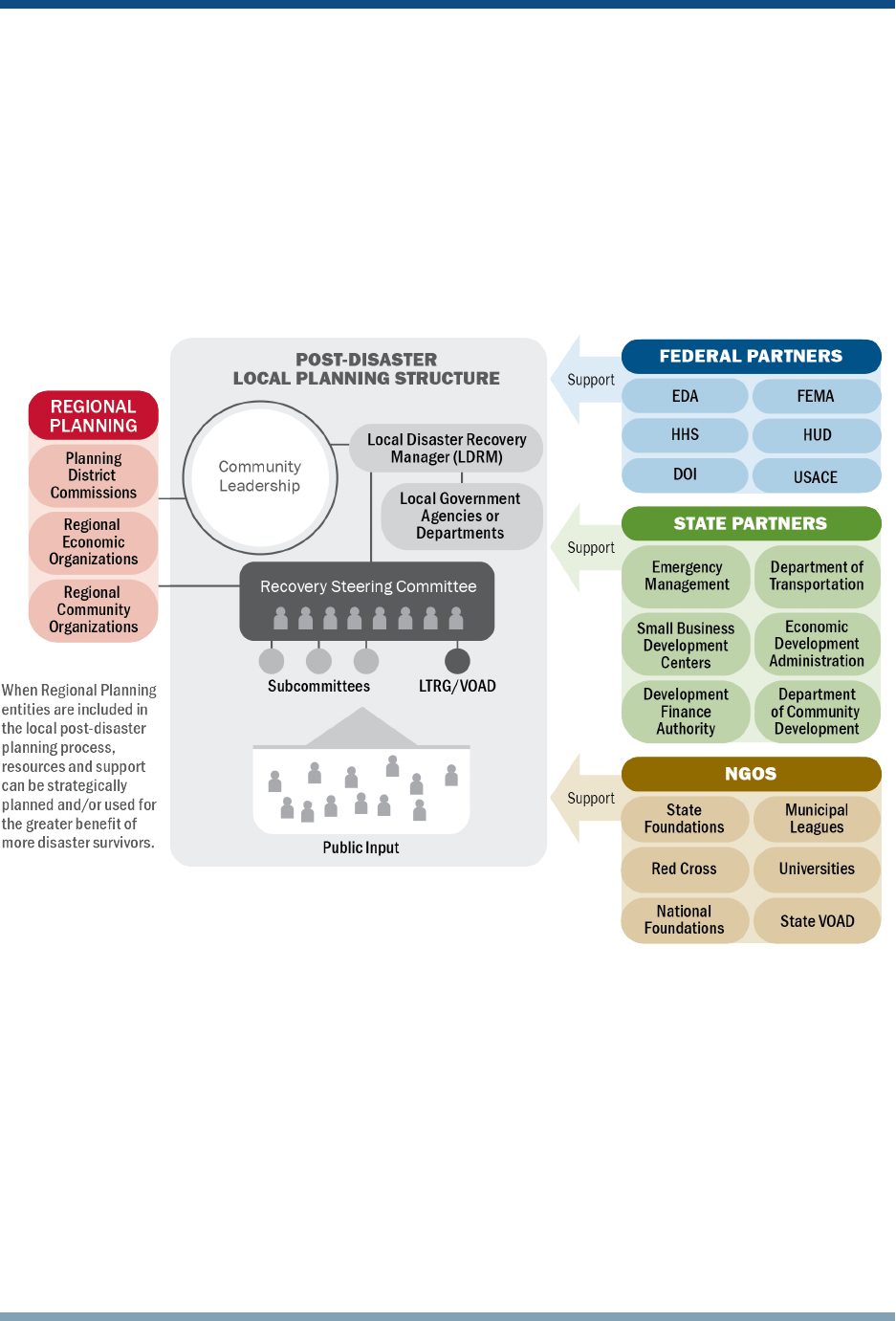

Figure 9 Post-disaster Local Planning Structure ..........................................................................................52

Figure 10 Pre-disaster Recovery Plan Components......................................................................................61

Figure 11 The Relationship between this Guidance and the Local Mitigation Planning Handbook ............73

Figure 12 Example Planning Timeline ........................................................................................................85

TABLES

Table 1 Pre- and Post-Disaster: Critical Planning Tasks ..............................................................................25

Table 2 Suggested Stakeholders and Partners for Recovery Core Capabilities ...............................................34

Table 3 Capacity Assessment Questions for Recovery Core Capabilities ......................................................44

Table 4 Sample Table of Risks and Mitigation Measures ..............................................................................83

Table 5 Sample Table of Partners and Their Responsibilities .......................................................................84

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page iv

Acronyms

The list below applies to acronyms used throughout the base document. Acronyms may be included in

Appendices and will be defined as they are used.

Acronym Definition

ADA Americans with Disabilities Act

APA American Planning Association

CARRI Community and Regional Resilience Institute

CPG Comprehensive Preparedness Guide

CRS Community Rating System

DHS Department of Homeland Security

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency

GCRC Galveston Community Recovery Committee

LDRM Local Disaster Recovery Manager

NDRF National Disaster Recovery Framework

NGO Nongovernmental Organization

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NFIP National Flood Insurance Program

NREL National Renewable Energy Laboratory

NVOAD National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters

PAS Planning Advisory Service

PDRP Post-Disaster Redevelopment Plan

PPD Presidential Policy Directive

PRA Priority Redevelopment Area

RSF Recovery Support Function

THIRA Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

VOAD Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters

Page 1

I. Introduction

This planning guide is designed to help local governments prepare for recovery by developing pre-disaster

recovery plans that follow a process to engage members of the whole community, develop recovery

capabilities across governmental and nongovernmental partners, and ultimately create an organizational

framework for comprehensive local recovery efforts.

Disasters in the United States result in billions of dollars in damage and disrupt the lives of untold numbers

of citizens each year. According to the Center for American Progress, in 2011 and 2012 alone, 1,107 fatalities

and up to $188 billion in economic damage were the result of extreme weather events.

1

Although some

areas are more susceptible to disasters than others, no area is perfectly safe and all communities need to be

prepared for recovery after a disaster strikes.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA) works to ensure that communities have the

tools needed to make informed decisions to reduce

risks and vulnerabilities and to effectively respond

and recover. Effective pre-disaster planning is an

important process that allows a comprehensive and

integrated understanding of community objectives.

Pre-disaster planning also connects community plans

to guide post-disaster decisions and investments. This

guide will aid in understanding the key considerations and process that a local government can use to build

a community’s recovery capacity and develop a pre-disaster recovery plan.

The ability of a community to successfully manage the recovery process begins with its efforts in

pre-disaster preparedness, mitigation, and recovery capacity building. These efforts result in resilient

communities with an improved ability to withstand, respond to, and recover from disasters. Pre-disaster

recovery planning promotes a process in which the whole community fully engages with and considers

the needs and resources of all its members. The community will provide leadership in developing recovery

priorities and activities that are realistic, well planned, and clearly communicated.

Local leadership is a key element of the national approach to disaster recovery embodied in the National

Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF)

3

, which is the national framework designed to support effective recovery

in disaster-impacted communities. The NDRF acknowledges that successful recovery depends heavily on

local planning, local leadership, and the whole community of stakeholders with an interest in recovery.

The NDRF emphasizes principles of preparedness, sustainability, resilience, and mitigation as integral to

successful recovery outcomes. These themes are highlighted throughout this guide.

“Without a comprehensive, long-term recovery

plan, ad hoc efforts in the aftermath of a signicant

disaster will delay the return of community stability.

Creating a process to make smart post-disaster

decisions and prepare for long-term recovery

requirements enables a community to do more than

react….”

2

1

Daniel J. Weiss and Jackie Weidman, Disastrous Spending: Federal Disaster: Relief Expenditures Rise amid More Extreme Weather, (Washington: Center for

American Progress, 2013), available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/green/report/2013/04/29/61633/disastrous-spending-Federal-disaster-relief-

expenditures-rise-amid-more-extreme-weather/

2

Florida Department of Community Affairs / Florida Division of Emergency Management, Post-Disaster Redevelopment Planning: A Guide for Florida Communities

(2010), p. 4.

3

FEMA, National Disaster Recovery Framework (2016). http://www.fema.gov/national-disaster-recovery-framework-0.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 2

Primary Sources for this Guide

Information provided in this Guide is drawn primarily from and builds on the general planning concepts in the following

documents, among others:

• National Disaster Recovery Framework (FEMA)

• National Mitigation Framework (DHS)

• Developing and Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans: Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101 (FEMA)

• PAS 576: Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery (APA)

• PAS 560: Integrating Hazard Mitigation into Local Planning (APA)

• Long-Term Community Recovery Planning Process: A Self-Help Guide (FEMA)

• Threat and Hazard Identication and Risk Assessment Guide: Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 201 (DHS)

• A Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management Themes and Pathways for Action (FEMA)

Successful community recovery is broader than simply restoring the infrastructure, services, economy and

tax base, housing, and physical environment. Recovery also encompasses re-establishing civic and social

leadership, providing a continuum of care to meet the needs of affected community members, reestablishing

the social fabric, and positioning the community to meet the needs of the future. Encouraging a town or city

to make progress toward recovery efforts may be difficult, particularly after a catastrophic disaster. Preparation

efforts are critical to ensuring that leadership, government, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)

are ready to act quickly. A community comprises a variety of partners, including economic development

professionals, business leaders, affordable housing advocates, faith-based organizations, and functional and

access needs populations, and each has a significant part to play in recovery.

At a fundamental level, disaster recovery requires balancing practical matters with broad policy

opportunities. Communities must be ready to invest significant effort to understand and acclimate to the

new conditions and growth opportunities post-disaster and to create a desirable future based on these

circumstances. Doing these things successfully requires the community to undertake a structured recovery

planning process after the disaster, through which the community develops a vision for itself, sets goals,

and identifies concrete methods for reaching these goals. Without an organized community planning

process that is ready to be implemented post-disaster, recovery may occur but is likely to be uneven, slow,

and inefficient.

Pre-disaster planning ensures that an affected community is ready to undertake an organized process

and does not miss opportunities to rebuild in a sustainable, resilient way. With a planning framework in

place (developed using this guide), a community is better situated to address pre-existing local needs,

take advantage of available resources, and seize opportunities to increase local resiliency, sustainability,

accessibility, and social equity. By working in advance to develop an understanding of needs and

vulnerabilities, identify leaders, form partnerships, establish resources, and reach consensus on goals and

policies, communities will be prepared to begin recovery immediately rather than struggle through a

planning process in the wake of a disaster.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 3

Why Prepare a Local Pre-Disaster Recovery Plan?

• Establish clear leadership roles, including the mayor’s

ofce, city manager, and city council, for more decisive

and early leadership.

• Improve public condence in leadership through early,

ongoing, and consistent communication of short- and

long-term priorities.

• Avoid the often difcult, ad hoc process of post-disaster

discovery of new roles, resources, and roadblocks.

• Gain support from whole-community partnerships

necessary to support individuals, businesses, and

organizations.

• Improve stakeholder and disaster survivor involvement

after the disaster through a denition of outreach

resources and two-way communication methods the

local government and key organizations will employ.

• Maximize Federal, State, private-sector, and

nongovernmental dollars through early and more dened

local priorities and post-disaster planning activity.

• Provide for more rapid and effective access to Federal

and State resources through better understanding of

funding resources and requirements ahead of time.

• Enable local leadership to bring to bear all capability

and more easily identify gaps through a coordination

structure and dened roles.

• Better leverage and apply limited State and

nongovernment resources when there is no Federal

disaster declaration.

• Maximize opportunities to build resilience and risk

reduction into all aspects of rebuilding.

• Speed identication of local recovery needs and

resources and ultimately reduce costs and disruption

that result from chaotic, ad hoc, or inefcient allocation

of resources.

• Improve capability and continuity through pre-

identication of when, where, and how the local

government will employ and seek support for

post-disaster planning, city operations, recovery

management, and technical assistance.

• Proactively confront recovery and redevelopment policy

choices in the deliberative and less contentious pre-

disaster environment.

• Improve the ability to interface with State and Federal

Recovery Support Function structure.

Douglas County, CO, Disaster Recovery Plan

In 2015, ofcials in Douglas County, CO, adopted the county’s rst Disaster Recovery Plan. The plan establishes the

county’s comprehensive framework for managing recovery efforts following a major disaster. The plan is also linked to a

previously developed Continuity of Operations Plan to facilitate successful disaster recovery.

“Having been through our own wildres, oods, and other local emergencies, as well as having witnessed other counties

navigate their own disasters, our staff had the foresight to recognize the importance of collaboration among our

partners to assemble a recovery plan,” said Commissioner David Weaver. “By focusing on what could occur instead of

what is or already has happened, places Douglas County in the best possible shape to react to any potential disaster, be

it man-made or natural.

6

4

FEMA, Developing and Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans: Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101: (2010). http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.

do?=&id=5697.

5

FEMA, Local Mitigation Planning Handbook (2013). https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1910-25045-9160/fema_local_mitigation_handbook.pdf.

6

“County Adopts Disaster Recovery Plan” (March 20, 2015), http://www.douglas.co.us/county-adopts-disaster-recovery-plan/).

For more information, see the Douglas County Disaster Recovery Plan at http://www.douglas.co.us/documents/douglas-county-recovery-plan.pdf.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 4

PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE

This guide is designed to help local governments work with community stakeholders to develop a

recovery plan that includes recovery roles and capabilities, organizational frameworks, and specific

policies and plans. Using a step-by-step discussion of the planning process, this guide introduces

principles underlying preparedness and recovery planning, describes topics to be considered as part of the

planning process, and identifies specific or

ganization-building and planning activities.

Achieving fundamental recovery preparedness, involves application of six standard planning process steps

as well as several associated key recovery activities. The key activities are intended to serve as additional

considerations that expand on the overarching six planning steps, as illustrated in the graphic below, and

focus more specifically on the challenges and unique partnerships necessary for successful pre-disaster

recovery planning. In the following chapters this guide provides guidance for applying these steps and

activities in a scalable fashion in large to small communities.

The planning process introduced and discussed in this guide directly aligns with the process outlined in

Developing and Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans: Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101 (CPG 101). This guide is

formatted to follow the six steps of CPG 101 and presents six standard planning steps in Chapters 7 through

12 and then presents key recommended activities that are specific to pre-disaster recovery planning efforts.

Figure 1 can help to serve as a basic orienting checklist for preparing for recovery.

Figure 1 Key Activities in the Pre-disaster Recovery Planning Process

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 5

Additionally, the considerations in this guide reflect the best practices and general sequence of other

planning guidance documents, such as the Local Mitigation Planning Handbook. Similarities among these processes

are discussed throughout this guide and are outlined in Appendix A of this guide.

Completing this process results in a pre-disaster recovery plan that provides a local-level framework for

leading, operating, organizing, and managing resources for post-disaster recovery activities. The plan

can then be used to implement the post-disaster recovery process and carry out post-disaster planning

and management of recovery activities, such as restoring housing, rebuilding schools and child care

services, recovering businesses, identifying resources for rebuilding projects, returning social stability,

and coordinating other community planning processes. This guide will also assist communities with the

creation of other tools, such as recovery ordinances, that support recovery activities.

AUDIENCE

The primary target audiences for this guide are local government officials and planners taking an active

role in organizing or managing the development of a recovery plan. Their titles can vary from

community to community but generally include community, economic, urban or emergency

management planners; key departmental staff and officials such as housing departments or authorities;

and city managers. Secondary audiences include organizations that represent key stakeholders in the

community, such as disability, cutural, social services or other interest groups. These secondary

audiences might also include local partners who have responsibility, oversight, or authority (formal or

informal) to manage resources, policies, programs, infrastructure, and institutions significant to the

recovery process.

Successful planning for recovery requires participation by local government and community leaders,

officials, organizations, and individuals who are able and ready to take responsibility for shaping the

future of their community. Additionally, government and community leaders who are involved in pre-

disaster recovery planning should have the ability to encourage participation from all segments of the

community. While this guide is more extensive than that needed for leadership, a key role of the planner

will be to take key materials and concepts in this guide to educate and inspire community leaders to

support the development and implementation of the recovery planning. The tools and resources

accompanying this guide located at www.fema.gov/plan will include an overview for use with

community leadership

Regional or county level agencies, councils or commissions may also be a potential audience.

This guide

acknowledges that some communities have more capacity and capability to address pre-disaster recovery

preparation than others do. While the primary responsibility for the planning process is at the local level,

emphasis is placed on identifying partners and resource providers able to collaborate with or supplement

local capacity. A regional or multi-jurisdictional effort may be appropriate where resources are more

limited.

Page 6

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Page 7

II. National Recovery

Preparedness Efforts

A number of Federal initiatives are designed to assist all levels of government, as well as businesses,

individuals, and families with disaster preparedness activities. This guide is one element among these

initiatives. Information on these national efforts is summarized below.

PRESIDENTIAL POLICY DIRECTIVE 8

Presidential Policy Directive 8:

6

National Preparedness, describes the Nation’s approach to preparing for the threats

and hazards it faces. At its core, PPD-8 requires the involvement of the whole community in a systematic

effort to keep the Nation safe from harm and resilient when struck by natural disasters, acts of terrorism,

pandemics, and other disasters. It directs the development of a National Preparedness Goal.

7

This guide supports

that goal at the local level by providing guidance to local government stakeholders for pre-disaster recovery

planning.

NATIONAL PREPAREDNESS GOAL

The National Preparedness Goal defines what it means for a whole community to be prepared for all types of

disasters and emergencies. The National Preparedness Goal is:

“A secure and resilient nation with the capabilities required across the whole community to prevent, protect

against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from the threats and hazards that pose the greatest risk.”

8

The National Preparedness Goal identifies five mission areas (Prevention, Protection, Mitigation, Response,

and Recovery) to organize preparedness activities. Within these mission areas, the National Preparedness Goal

defines the Core Capabilities that are necessary to prepare for the types of risks and hazards that pose the

greatest risk to the security of the Nation. Core Capabilities represent the competencies necessary for the

timely restoration, strengthening, and revitalization of communities impacted by a catastrophic disaster.

The National Preparedness Goal, along with the NDRF and all other frameworks, was refreshed in 2015 and 2016

to address lessons learned through implementation and stakeholder feedback. A number of new guidance

documents will help the public, businesses, NGOs, and all levels of government make the most of their

preparedness activities. This guide supports the achievement of this goal at the local level by providing

additional guidance to local governments for pre-disaster recovery planning to augment information in the

National Preparedness Goal and the NDRF.

6

Presidential Policy Directive 8: National Preparedness (2015): https://www.fema.gov/learn-about-presidential-policy-directive-8

7

DHS, National Preparedness Goal (2015): http://www.fema.gov/national-preparedness-goal

8

DHS, National Preparedness Goal, p.1.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 8

PPD-8 requires an annual National Preparedness

Report that summarizes national progress in

building, sustaining, and delivering the Core

Capabilities outlined in the National Preparedness

Goal. The intent of the National Preparedness

Report is to provide the Nation—not just the

Federal Government—with practical insights

on Core Capabilities that can inform decisions

about program priorities, resource allocation,

and community actions. Since 2012, the Core

Capabilities within the Recovery Mission Area have

consistently emerged as areas for improvement.

Recovery Core Capabilities include Planning,

Public Information and Warning, Operational

Coordination, Economic Recovery, Health and

Social Services, Housing, Infrastructure Systems,

and Natural and Cultural Resources. Additionally,

many of the Mitigation Core Capabilities, such

as the incorporation of Long-Term Vulnerability

Reduction and Community Resilience into the

planning process, are intrinsically linked to

successful pre-disaster recovery planning. This

guide describes the process for delivering the

Recovery Core Capabilities at the local government

level. All of the Core Capabilities are discussed in

more detail throughout this guide and at https://

ww

w.fema.gov/core-capabilities.

NATIONAL DISASTER RECOVERY

FRAMEWORK

The NDRF provides recommendations on the local

role in preparing for and implementing recovery.

It also identifies guiding principles, best practices,

and expectations to enable efficient and effective

recovery support and coordination for the whole

community. It is built on a scalable, flexible, and

adaptable coordinating structure to align key

roles and responsibilities to deliver the necessary

capabilities. As such, it is a valuable resource to

help local stakeholders understand the practices

and guidelines followed by Federal agencies in

supporting disaster recovery. The NDRF also

identifies strategies that can be used to inform local

recovery planning. In addition to these strategies,

the NDRF identifies leadership responsibilities at the

local, State, tribal, and Federal levels.

Discussion Point:

Recovery Core Capabilities

The National Preparedness Goal denes eight Core

Capabilities that apply to the Recovery Mission Area.

The efforts of the whole community – not any one

level of government – are required to build, sustain,

and deliver the Core Capabilities.

• Planning – Conduct a systematic process engaging

the whole community as appropriate in the

d

evelopment of executable strategic, operational,

and/or tactical approaches to meet dene

d

objectives.

• Public Information and Warning – Deliver

coordinated, prompt, reliable, and actionable

in

formation to the whole community through

the use of clear, consistent, accessible, and

culturally and linguistically appropriate methods to

e

ffectively relay information regarding any threat

or hazard and, as appropriate, the actions being

taken and the assistance being made available.

• Operational Coordination – Establish and maintain

a unied and coordinated operational structure

a

nd process that appropriately integrates all

critical stakeholders and supports the execution o

f

core capabilities.

• Economic Recovery – Return economic and

business activities (including food and agriculture)

to a healthy state and develop new business

and employment opportunities that result in a

sustainable and economically viable community.

• Health and Social Services – Restore and improve

health and social services capabilities and

networks to promote the resilience, independence,

h

ealth (including behavioral health), and well-being

of the whole community.

• Housing – Implement housing solutions that

effectively support the needs of the whole

c

ommunity and contribute to its sustainability and

resilience.

• Infrastructure Systems – Stabilize critical

infrastructure functions, minimize health and

safety threats, and efciently restore and revitalize

s

ystems and services to support a viable, resilient

community.

• Natural and Cultural Resources – Protect natural

and cultural resources and historic properties

through appropriate planning, mitigation, response,

a

nd recovery actions to preserve, conserve,

rehabilitate, and restore them consistent with post-

d

isaster community priorities and best practices

and in compliance with appropriate environmental

and historic preservation laws and Executive

Orders.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 9

A key feature of the NDRF is its use of Recovery Support

Functions (RSFs) to organize Federal resources. The

six RSFs (Community Planning and Capacity Building,

Economic, Health and Social Services, Housing,

Infrastructure Systems, and Natural and Cultural

Resources) are intended to promote a flexible recovery

structure at the Federal level; they are designed to

support local, State, and tribal recovery structures. The

NDRF also identifies factors that facilitate a successful

recovery, such as resilient rebuilding, effective decision-

making, and coordination. These factors are expanded

on in Appendix C. Finally, an NDRF Overview Course is

available through the Emergency Management Institute.

9

NATIONAL MITIGATION FRAMEWORK

The National Mitigation Framework

10

establishes a common

platform and forum for coordinating and addressing how the Nation manages risk through mitigation

capabilities. Mitigation reduces the impact of disasters by supporting protection and prevention activities,

easing response, and speeding recovery to create better prepared and more resilient communities.

During the recovery planning and coordination process, actions can be taken to address the resilience of tribal

or local communities. The NDRF defines resilience as the ability to adapt to changing conditions and withstand

and rapidly recover from disruption due to emergencies, while mitigation includes the capabilities necessary to

reduce loss of life and property by lessening the impact of a disaster. Consideration should be given to integrating

the National Mitigation Framework and Mitigation Core Capabilities into the structure, policies, and roles developed

during the course of building a local recovery plan. A recovery plan can contain important elements to

operationalize the Mitigation Core Capabilities during the recovery period. The best way to integrate mitigation

activities is to link the recovery plan with the local hazard mitigation plan.

Discussion Point:

Mitigation Core Capabilities

The National Preparedness Goal denes seven Core

Capabilities that apply to the Mitigation Mission

Areas. The rst three are common Core Capabilities,

shared with all mission areas.

• Planning

• Public Information and Warning

• Operational Coordination

• Community Resilience

• Long-Term Vulnerability Reduction

• Risk and Disaster Resilience Assessment

• Threats and Hazards Identication

Key References to Use in Conjunction with this Guide

• Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery: Next Generation (PAS Report 576), APA

Provides extensive information and examples for organizing, planning, managing, and implementing recovery. Also

includes a resource library and model recovery ordinance. https://www.planning.org/research/postdisaster/

• Community Resilience Planning Guide for Infrastructure and Buildings, NIST

Follows the same six-step planning construct used in this guide, helps bridge physical planning for infrastructure

resilience with the social and organizational dimensions of the community, and provides a method to evaluate

and set recovery goals for return of functioning infrastructure that can help drive recovery as well as pre-disaster

mitigation. http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1190v1.pdf.

• Local Mitigation Planning Handbook, FEMA

Provides guidance for the required local hazard mitigation plans and links to risk assessment resources. http://www.

fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=7209.

• Effective Coordination of Recovery Resources for State, Tribal, Territorial and Local Incidents, FEMA

Provides examples and guidance for building whole-community partnerships and coordination structure at the local,

State, tribal, and Federal levels to serve recovery. https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/101940

aspx?code=IS-2900.

10

DHS, National Mitigation Framework (2016). https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1466014166147-11a14dee807e1ebc67cd9b74c6c64bb3/National_

Mitigation_Framework2nd.pdf.

9

An independent study course called “National Disaster Recovery Framework Overview” is available at http://training.fema.gov/is/courseoverview.

Page 10

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Page 11

III. Key Concepts for Recovery

Planning

Through years of national, State, tribal, and local experience implementing community disaster recovery

efforts, several key concepts have emerged that serve as a foundation for successful pre- and post-disaster

recovery planning. These concepts, discussed briefly below, are expanded upon throughout the NDRF.

RECOVERY ACTIVITIES ARE LOCALLY DRIVEN

First and foremost, recovery planning should be driven by the community. The NDRF emphasizes, as one

of its nine principles, the concept and importance of local leadership and local primacy. Local governments,

businesses, NGOs, and their community members in particular have the primary responsibility for

many recovery decisions, investments, and actions. Therefore, local governments serve in the lead role in

planning for and managing many aspects of community recovery. Local recovery organizational structure

must have a direct nexus with local government. Local input is also needed by State, tribal, and Federal

partners so that they can design programs and policies to meet local needs.

11

In some cases, it may be difficult for the community to take on significant responsibility for the recovery

process because of lack of capacity, resources, staff, or other factors. External partners may need to support

recovery planning, outreach, communication, and implementation activities. However, this support must

still be guided by community leaders, the local government, and a broad range of community stakeholders.

Care must be taken to ensure that support is applied where necessary, beginning immediately after disaster

strikes and continuing through challenging redevelopment decisions.

Case Example: Community-Driven Recovery - Galveston, TX

The ability of the local community to lead, manage, and implement its own recovery process is central to the success of

long-term recovery. Technical assistance from outside partners can support the community’s efforts, but local vision is

necessary to guide the process, and local capacity is needed to maintain momentum over the months or years required

for complete recovery.

To guide recovery from Hurricanes Gustav and Ike, City of Galveston leaders created the Galveston Community Recovery

Committee (GCRC), which included 330 city-appointed representatives serving on ve focus groups (Economic;

Environment; Housing and Community Character; Human Services; and Infrastructure, Transportation, and Mitigation).

Beginning in January 2009, the GCRC worked with Federal, State, and local partners over a 12-week period to develop a

recovery plan. GCRC continued to meet periodically over the next 2 years, during which, implementation of 30 of the 42

projects in the original plan commenced.

Pre-disaster planning can help communities develop the organization, leadership, and stakeholder engagement

necessary to carry out a process such as the one undertaken in Galveston after Hurricane Ike. Establishing these

aspects of the recovery process before the disaster increases the community’s resilience and speeds recovery efforts.

11

Appendix B of this document includes further explanation of the integration of State and local resources during recovery.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 12

DISASTER RECOVERY PLANNING IS A

BROAD, INCLUSIVE PROCESS

Preparedness is a shared responsibility, and it is

important that planning be a whole-community

activity involving individuals; businesses; faith-based

and community organizations; nonprofit groups;

schools and academia; media outlets; cultural,

environmental, and recreational organizations; and

all levels of government. Participation of all parts of

the community strengthens the planning process

and facilitates an equitable implementation after

a disaster strikes. Broad participation is especially

important because buy-in from community

members and organizations is strengthened by

an inclusive process. Recovery planning must

also involve stakeholders and elements of local

government not typically involved in emergency

planning, including economic development,

housing advocates and homeless organizations,

insurance companies, lenders, apartment owners

associations, environmental and historic preservation

stakeholders, and many others. Inclusion is necessary

to ensure that all aspects of a community are

considered.

Whole Community

As a concept, Whole Community is a means by which

residents, emergency management practitioners,

organizational and community leaders, and

government ofcials can collectively understand and

assess the needs of their respective communities and

determine the best ways to organize and strengthen

their assets, capacities, and interests. By doing

so, a more effective path to societal security and

resilience is built. In a sense, Whole Community

is a philosophical approach on how to think about

conducting emergency management.

There are many different kinds of communities,

including communities of place, interest, belief, and

circumstance, that can exist both geographically and

virtually (e.g., online forums). A Whole Community

approach attempts to engage the full capacity of the

private and nonprot sectors, including businesses,

faith-based and disability organizations, minority

and underserved or under-represented populations,

and the general public, in conjunction with the

participation of local, tribal, State, territorial, and

Federal governmental partners. This engagement

means different things to different groups. In an

all-hazards environment, individuals and institutions

make different decisions on how to prepare for

and respond to threats and hazards; therefore,

a community’s level of preparedness will vary.

The challenge for those engaged in emergency

management is to understand how to work with the

diversity of groups and organizations and the policies

and practices that emerge from them in an effort

to improve the ability of local residents to prevent,

protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from

any type of threat or hazard effectively.

12

Case Example: City of Pembroke Pines and Seminole Tribe of Florida Mutual Aid

Agreements - Pembroke Pines, FL

Many local governments have mutual aid agreements with neighboring tribes. These governments and tribes look to one

another for assistance on a day-to-day basis for routine emergencies, and would also look to one another after a disaster.

In Florida, for example, the Seminole Tribe of Florida has mutual aid agreements with at least ve other counties that are

outlined in State, local, and tribal laws and policies.

Keeping these pre-existing agreements in mind, local recovery planning teams should include representatives from

neighboring tribes.

13

12

For more information about the Whole Community approach, see FEMA’s A Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management: Principles, Themes, and

Pathways for Action. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1813-25045-0649/whole_community_dec2011__2_.pdf.

13

For more information about tribal-local government mutual aid agreements, see https://ppines.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2229607&GUID=4F5DA8FA-

B5C5-44F3-87AE-091765AE800C&Options=&Search=.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 13

As emphasized in the U.S. Department of Justice’s An ADA Guide for Local

Governments,

14

recovery planning, both before and after a disaster, must

include people with disabilities and others with access and functional

needs from the beginning to prevent delays or exclusion in post-disaster

recovery efforts. For example, affected populations may need to relocate,

and including these stakeholders in pre- and post-disaster planning

processes helps to better integrate their needs into plans and recovery

actions. Maximum efforts should be made to ensure that community

members whose involvement has historically been low are encouraged

to participate. Youth, for example, can often convey the preparedness

message more strongly than others in the community. Emphasis should

also be placed on including seniors, individuals with disabilities, and

others with access and functional needs

15

; those from religious, racial,

and ethnically diverse backgrounds; and people with limited English

proficiency. To ensure full and meaningful participation, there must

be physical, programmatic, and communication access for all those

potentially affected by a disaster.

Partnerships with regional, State, tribal, and Federal agencies and

organizations are important for recovery planning and post-disaster recovery because disasters can stress

even the most prepared or equipped local community, and partnerships offer a multitude of mutually

beneficial resources. Mutual aid agreements between local governments, councils of governments, tribes,

and regional planning entities are one way partnerships can help alleviate the burden of recovery. Others

include technical assistance from universities, financial assistance from NGOs and charitable organizations,

various other assistance from existing long-term recovery groups, and volunteer assistance from Volunteer

Organizations Active in Disasters (VOAD).

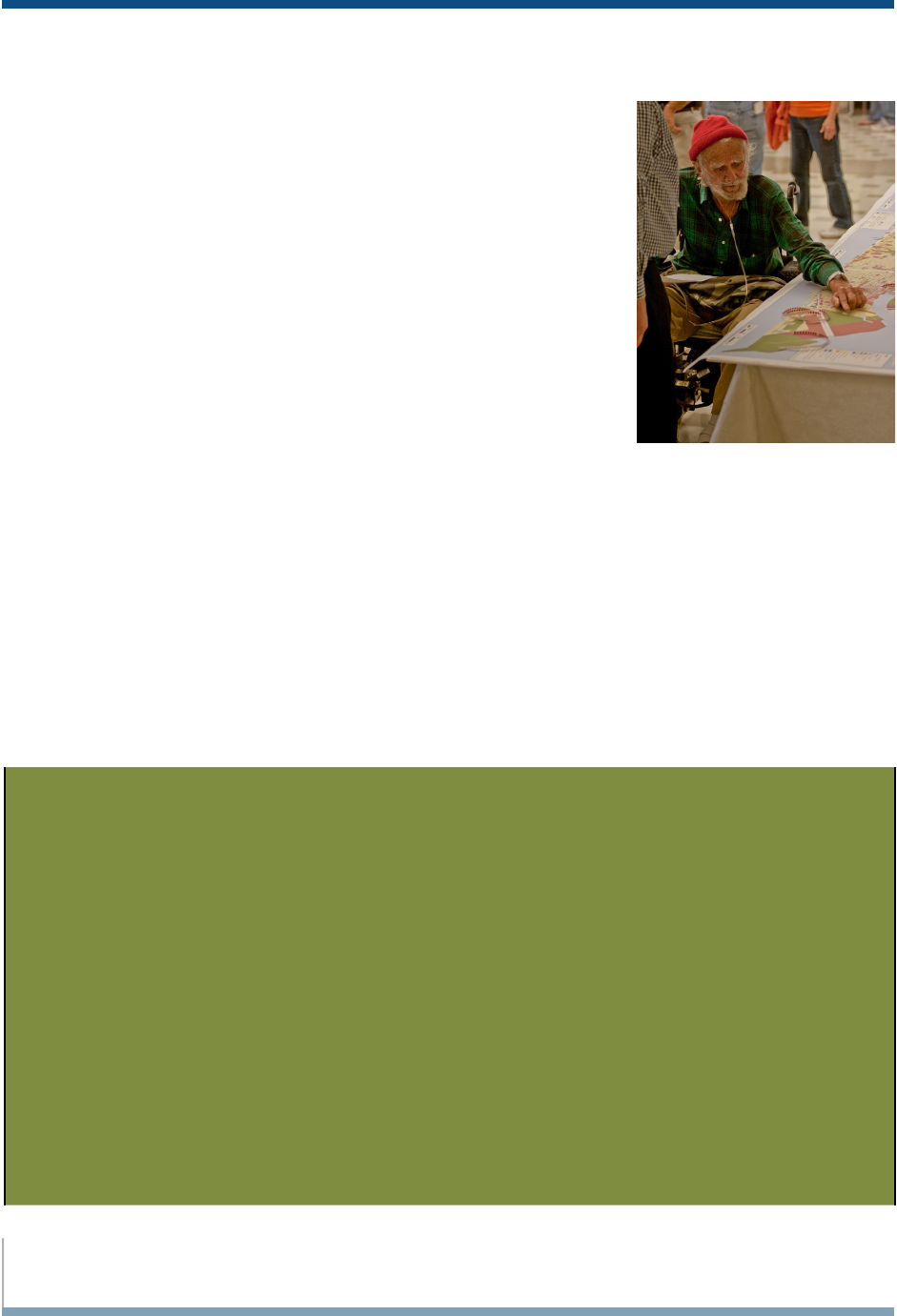

Galveston, TX: Community

resident participates in a recovery

planning session, learning about

where he lives, risk and recovery

issues.

Discussion Point: Equity in Disaster Planning and Recovery

Disasters can disproportionately affect some members of the community, including low-income, aging, functional and

access needs, and minority populations. These groups are more likely to be displaced and have more limited access

to resources, mobility issues, or difculty participating or being represented in recovery planning and community

activities. The planning process should evaluate the risk of these groups and their likelihood of displacement and

establish a strategy for basic communication, as well as a plan for ensuring equal participation in post-disaster

recovery planning and decisions.

For example, housing construction costs and replacement home values are likely to increase as a result of increased

demand and reduced supply in a signicant disaster. This can disproportionately affect the ability of the low- or

xed-income residents to nd adequate and safe housing. Hazard mitigation strategies used after a disaster, such as

buyouts, can also have the effect of reducing the stock of affordable housing if housing redevelopment plans are not

adequately addressed. The community’s affordable and fair housing plans should be coordinated with its recovery plan

to ensure that all residents can participate and are served in recovery and that workforce housing can be replaced. For

communities receiving Community Development Block Grant funds, the Consolidated Plan can also address recovery

and resilience issues.

Housing support or mitigation programs should take care to ensure equal access where possible. In some cases,

resources from Federal, State, or non-governmental agencies can be used to augment housing or mitigation programs

to encourage the participation of these groups or assist in the redevelopment of affordable housing in safe areas.

14

U.S. Department of Justice, An ADA Guide for Local Governments: Making Community Emergency Preparedness and Response Programs Accessible to People

with Disabilities (n.d.). http://www.ada.gov/emerprepguideprt.pdf.

15

People with disabilities and other people with access and functional needs must be able to access the same programs and services as the general population.

Providing access may require including modications to programs, policies, procedures, architecture, equipment, services, supplies, and communication methods.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 14

RECOVERY PLANNING BUILDS UPON AND IS INTEGRATED WITH OTHER

COMMUNITY PLANS

The planning process should incorporate the results of other applicable planning processes in the

community and region. Hazard mitigation plans, comprehensive plans, housing plans, and other

planning documents can define a wide range of goals for the community and represent shared priorities

of community members. Linking recovery planning to build on the community’s existing plans helps

inform recovery planning efforts and capitalize on past planning efforts so as not to “reinvent the wheel.”

Additionally, linking recovery planning with other applicable planning processes helps to incorporate

community perspectives. Recovery activities can then in turn be used to inform revisions to the

community’s other plans. Including the whole community in the pre-disaster recovery planning process

means including all sectors of the community.

Many existing Federal programs relate to disaster recovery. While many of these programs are voluntary for

communities, the requirements for participation could benefit communities when they develop their pre-

disaster recovery plan. For example, the Economic Development Administration requires communities to

produce Community Economic Development Strategies, and the Department of Health and Human Services

has preparedness requirements for communities that relate to disaster recovery. A pre-disaster recovery

planning process would build upon these existing efforts.

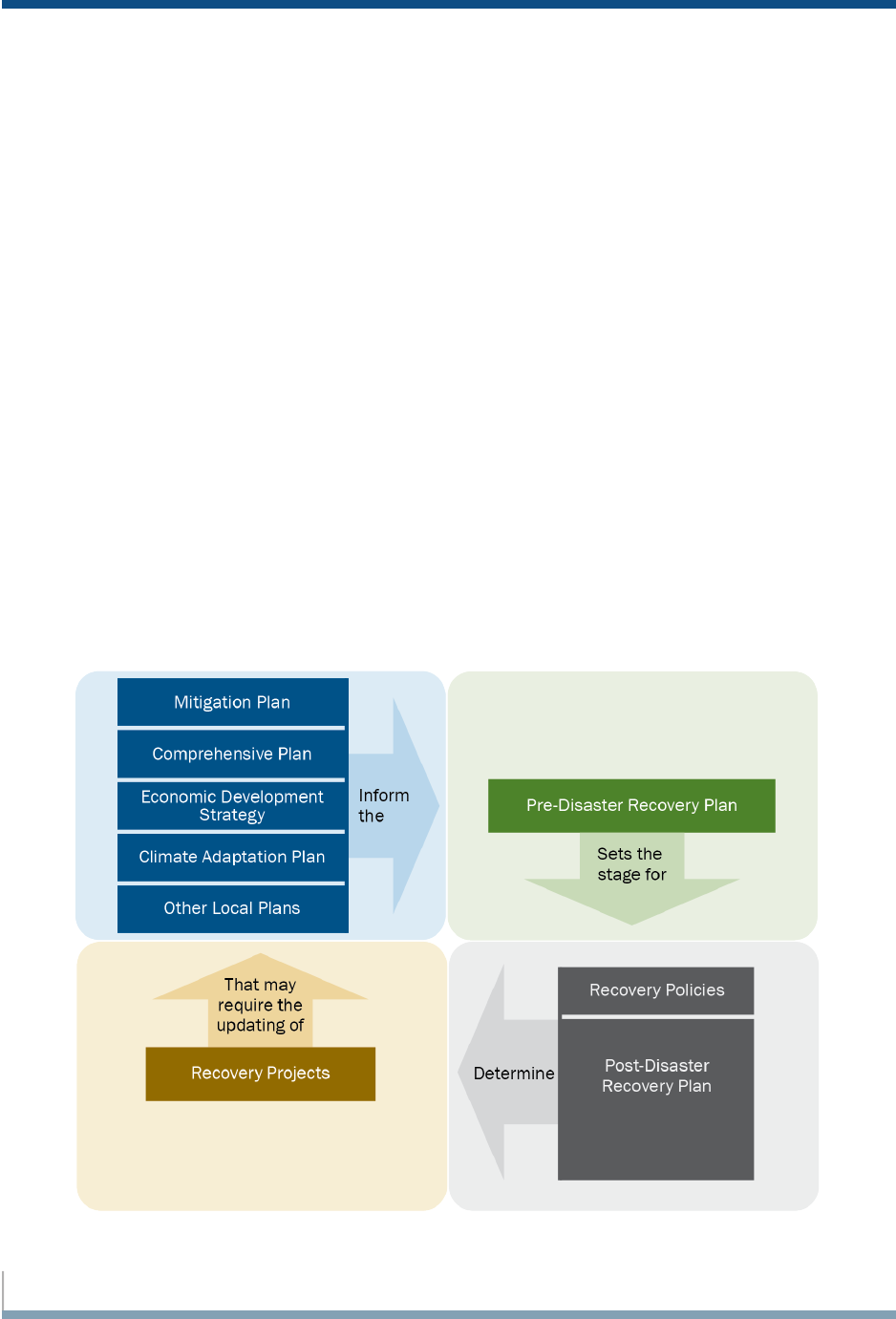

Figure 2 outlines the relationship between existing plans, like those mentioned above, and the pre-disaster

recovery plan. In addition, the figure explains how these existing plans and the pre-disaster recovery plan

are used after a disaster to support the development of post-disaster recovery plans, policies, and projects.

Figure 2 The Cyclical Nature of Planning

16

Many of these voluntary programs have grants or other funding opportunities associated with them that can be used by communities to support recovery-focused

initiatives.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 15

RECOVERY PLANNING IS CLOSELY ALIGNED WITH HAZARD MITIGATION

A key goal of both hazard mitigation and recovery is increasing resilience, defined in the National Preparedness

Goal as “the ability to adapt to changing conditions and withstand and rapidly recover from disruption due

to emergencies.” Although these two activities differ in many respects, this shared objective of increased

resilience allows mitigation and recovery planning to reinforce one another and leverage greater benefits

within the development of plans, and programs or projects. Because both mitigation and recovery planning

can be carried out pre-disaster, there is generally ample time to coordinate activities and promote more

widespread attention to resilience. Recovery planning can support hazard mitigation and resilience building

by providing a post-disaster mechanism for implementation and integration into the roles, processes,

and decisions that occur in the complex recovery environment. Additionally, much of the analysis and

information involved in the development of mitigation plans can be used to inform the pre-disaster

recovery planning effort. (Note that while recovery planning can support hazard mitigation, the intent of

the pre-disaster recovery planning process is not to add to the community’s mitigation plan.)

The pre-disaster recovery planning process benefits from and builds on hazard mitigation as:

• The mitigation planning process identifies local

hazards, risks, exposure, and vulnerability;

• Implementation of mitigation policies and

strategies reduce the likelihood or degree of

disaster-related damage, decreasing demand on

resources post-disaster;

• The process identifies potential solutions to

future anticipated community problems; and

• Mitigation activities increase public awareness of

the need for disaster preparedness.

Pre-disaster planning efforts also increase resilience

by:

• Establishing partnerships, organizational

structures, communication resources, and access

to resources that promote a more rapid and

inclusive recovery process;

• Describing how hazard mitigation underlies all

considerations for reinvestment;

• Laying out a process for implementing activities

that will increase resilience; and

• Increasing awareness of resilience as an

important consideration in all community activities.

In many ways, the process outlined in this guide aligns closely to the steps contained in the Local Mitigation

Planning Handbook. The Key Activities presented in later sections of this guide and the tasks associated with

those Key Activities facilitate close coordination and collaboration across these two planning processes.

Appendix A compares the process outlined in this document and the process outlined in the Local

Mitigation Planning Handbook.

Discussion Point: Hazard Mitigation

Plans

Reviewing the community’s hazard mitigation plan is

a good way to prepare for the pre-disaster planning

process. The hazard mitigation plan identies likely

hazards and can be used to determine priority

activities and policies to be undertaken as part of

disaster recovery, when resources and opportunities

are available to rebuild in a more resilient fashion.

The local jurisdiction may have its own mitigation

plan or may have participated in a multi-jurisdictional

mitigation plan. The State Hazard Mitigation Ofcer

can be contacted if there are difculties locating a

plan.

The State hazard mitigation plan is also a good

resource. Much like the local or multi-jurisdictional

plan, the State plan will identify potential hazards as

well as State hazard mitigation goals, priorities, and

funding sources.

FEMA developed the Local Mitigation Planning

Handbook (2013) as step-by-step guidance for

developing a mitigation plan. Many of the steps in the

handbook apply to recovery preparation as well.

17

16

The handbook is available at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1910-25045-9160/fema_local_mitigation_handbook.pdf.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 16

Building Resilience into the Recovery Process – The National Mitigation Framework

Recovery offers a unique opportunity to reduce future risk. Following any disaster, recovery efforts can be leveraged

to implement solutions that increase community resilience in the economic, housing, natural and cultural resources,

infrastructure, and health and social services and government sectors. Well planned, inclusive, coordinated, and

executed solutions can build capacity and capability and enable a community to better manage future disasters.

The National Mitigation Framework establishes a common platform and forum for coordinating and addressing how

the Nation manages risk through mitigation. Mitigation reduces the impact of disasters by supporting protection

and prevention activities, easing response, and speeding recovery to create better prepared and more resilient

communities.

The mitigation and recovery mission areas focus on the same community systems—community capacity, economic,

health and social services, housing, infrastructure, and natural and cultural resources—to increase resilience. Cross-

mission area integration activities, such as planning, are essential to ensuring that risk avoidance and risk reduction

actions are taken during the recovery process. Communities have developed hazard mitigation plans that outline

strategies and priorities to further community resiliency through mitigation. Integrating mitigation actions into pre- and

post-disaster recovery plans also provides systematic risk management after a disaster, with effective strategies for an

efcient recovery process.

Recovery projects that increase resilience can be implemented in any of the community systems outlined above. For

instance, housing and infrastructure projects may increase resilience by rebuilding housing to meet new building

and accessibility codes that minimize future damage or relocating critical infrastructure out of hazardous areas.

Other resilience strategies could focus on diversifying the economy and bringing in sustainable industries or helping

community organizations to increase the resilience of all populations through preparedness efforts. Using innovative

solutions to meet recovery needs is an important consideration in developing recovery strategies. State, tribal,

territorial, and local communities can look to a wide range of organizations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation or

various university centers and research institutes, for help in increasing resiliency.

Lessons learned during the recovery process also inform future mitigation actions and pre-disaster recovery planning.

Linking recovery and mitigation breaks the cycle of damage-repair-damage resulting from rebuilding after disasters

without considering resilience.

RECOVERY PLANNING IS GOAL ORIENTED

Thorough, comprehensive, and community-supported pre-disaster recovery plans allow a locality to

more easily and effectively begin the recovery process immediately after a disaster. The development and

documentation of recovery planning goals, including the partnerships necessary to achieve those goals,

help recovery stakeholders understand existing capabilities and gaps. Equally important is the development

of realistic goals. Although a community may have its own resources or partner resources at its disposal,

the resources available to recover effectively are finite. Goal development in both the pre-disaster and

post-disaster environments needs to account for the availability of resources so that they may be leveraged

strategically to achieve desired outcomes. Appendix F includes a template that can be used to document

existing capabilities as they relate to recovery goals and the partnerships and resources in place (or not

currently in place) to achieve those goals.

In addition to determining capability gaps, using a goal-oriented process for pre-disaster recovery planning

helps to build consensus among the involved stakeholders. Establishing common, mutually agreeable,

strategic goals early in the planning process reduces conflicts when the plan is implemented in a post-

disaster setting.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 17

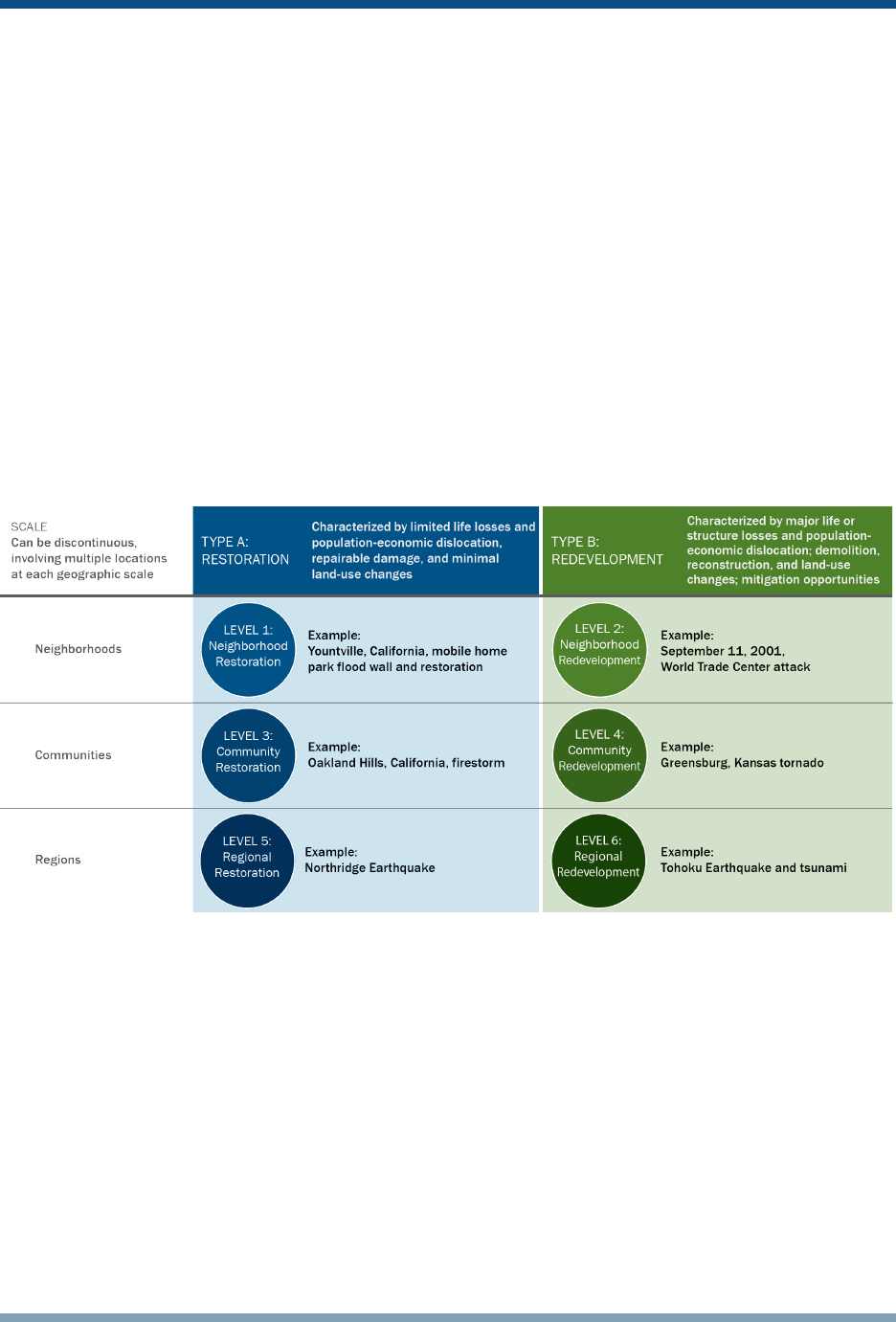

RECOVERY PLANNING IS SCALABLE

Recovery plan components should be scaled to meet both the capacity of the community to manage its own

recovery process and the level of risk the community faces. Communities that have minimal resources to

manage recovery but many vulnerabilities and risks will want to emphasize partnership-building in the

planning process and seek assistance from State or regional bodies. Communities with a high capacity to

manage recovery will want to emphasize local roles and responsibilities in facilitating the recovery process

and may be in a position to develop a robust recovery plan.

Pre-disaster recovery plan components such as recovery goals and policies, administrative structure, and

activation of personnel (see Appendix E) will vary depending on the capacity of the community and the

partnerships needed or already in place. Operational guidance included in the pre-disaster recovery plan

should also consider the different phases of disaster management, transition from or coordination with

response coordination structures, and identify times when recovery operations peak and when they begin

to wind down. An example of a scalable recovery system is shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 Scalable Recovery System

Source: Adapted from American Planning Association (APA) Planning Advisory Service (PAS) Report 576, page 53

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 18

Communities with limited capacity to plan for recovery and with low risk factors for disasters can

undertake certain basic planning activities that can lay the groundwork for recovery planning, and require

little staff time or funding. Examples of basic planning activities include:

• Committing to risk reduction and risk management

• Designating a point-person for recovery planning (ideally, someone who understands both emergency

management and community planning)

• Identifying vital facilities that, if damaged or destroyed, would have the strongest consequences to the

community (e.g., facilities used by the public, facilities that serve critical economic functions)

• Developing a public engagement strategy that is inclusive of the entire community’s population (this

also includes determining the best ways to communicate)

• Identifying existing recovery stakeholders (local agencies or organizations that would be critical to

facilitate the recovery process after a disaster)

• Identifying outside partnerships to build resilience (State agencies or other organizations that have

resources to support local recovery after a disaster)

• Identifying training programs that could help build the community’s capacity to plan for recovery

(these may include training offered by the State or independent study courses offered by the

Emergency Management Institute)

• Identifying key post-disaster responsibilities of local government and officials, not only for immediate

rebuilding, such as permitting requirements, but also for establishing a post-disaster strategy for

interim and long-term recovery

Basic planning activities generally involve the identification of people, partnerships, and programs that can

support the community’s recovery planning process.

Alternatively, communities that do have the capacity needed to plan for recovery, or communities facing

higher risk factors for disasters, can undertake more comprehensive planning activities in addition to the

basic activities listed above. Examples of comprehensive planning activities include:

• Developing recovery priorities based on existing plans and initiatives already in place (assessing

known planning goals that should be incorporated into recovery planning)

• Establishing a Local Disaster Recovery Manager (LDRM) position, office, and/or set of functions

• Conducting a vulnerability analysis (determining not only which facilities are critical, but how

vulnerable they are to disaster impacts and why they are vulnerable)

• Conducting an assessment of recovery capacity (reviewing resources available to support recovery

after a disaster and where there are gaps)

• Developing and adopting a recovery ordinance (a formal ordinance that describes how the

community will undertake the recovery process after a disaster)

• Developing a hazard mitigation plan (required by FEMA for most disaster assistance);

• Developing a formal, stand-alone pre-disaster recovery plan

• Formalizing mutual aid agreements with other jurisdictions to support long-term recovery needs

• Integrating resilience strategies into economic development, housing, infrastructure improvement,

historic preservation, health policies, and other regional or community programs and plans

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 19

Comprehensive planning activities require resources such as staff and possibly funding (though it is

noteworthy that developing an approved hazard mitigation plan can open the door to future funding

opportunities, which can be used to implement mitigation actions).

RECOVERY ACTIVITIES ARE COMPREHENSIVE AND LONG-TERM

The pre-disaster recovery planning process should address all of the Core Capabilities under Recovery

and Mitigation (see Section II.C of this guide for a list of Recovery Core Capabilities and Mitigation Core

Capabilities). Recovery activities may continue for months or years after a disaster, and the organizational

structure for overseeing recovery needs to be flexible and durable so the appropriate responsibilities can be

carried out. The recovery structure will need to change and adapt to the changing priorities and goals of

the community over the course of the many months and years of recovery operations.

RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY

A truly holistic recovery process must include activities that support building community resilience and

encouraging sustainable development. This concept can be implemented in recovery planning efforts

through coordination with mitigation planning. Mitigation is a sustained action eliminating or reducing

potential effects of hazards, and mitigation planning attempts to identify those hazards, reduce any impacts

from those hazards, and identify potential solutions. Thus mitigation planning, pre-disaster recovery

planning, and other types of planning have parallel perspectives with overarching recovery goals of:

• Increasing the speed of community recovery;

• Effectively using resources; and

• Increasing opportunities for community betterment that take into account and balance all community

populations, needs, and risks.

A successful mitigation program and other pre-disaster planning can set the stage for a more sustainable

and resilient community by positioning the community to be able to adapt to changing conditions, identify

future natural and human-related disaster threats and hazards, and withstand and rapidly recover from

disruption due to future emergencies. By addressing potential risks and developing solutions, policies, and

action statements, communities become both more resilient and sustainable.

Discussion Point: National Flood Insurance Program Community Rating System

The Community Rating System (CRS) was implemented in 1990 through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)

to recognize and encourage activities in communities that work to exceed the minimum standards of the NFIP. Through

the CRS, communities that take actions that meet the goals of the program are entitled to discounted rates for ood

insurance premiums. Many of the resilience and sustainability programs that communities either already engage in, or

seek to engage in as a part of recovery planning, complement the activities highlighted by CRS. By conducting planning

for recovery in coordination with mitigation and other resilience-focused programs, communities can see a tangible pre-

disaster benet through CRS.

16

16

For more information on the NFIP CRS, see https://www.fema.gov/national-ood-insurance-program-community-rating-system.

Page 20

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Page 21

IV. Linking Pre-Disaster Response

Planning and Pre-Disaster

Recovery Planning

Response and recovery are fundamentally different

and separate elements of disaster management,

but they are closely linked. Initially, when disaster

strikes, response takes the spotlight. Emergency

responders provide the most urgent and immediate

assistance to the disaster-impacted communities,

including food, water, shelter, debris clearance,

and medical attention. Response operations are

typically short-term, and usually focused on issues

of life safety and property protection. However,

recovery addresses the short-, intermediate-, and

long-term needs of an impacted community with a

focus on rebuilding for resilience. Recovery begins

during the response period when information is

gathered through damage assessments, ensuring

an early strategic focus on recovery. Coordination

with response operations is essential to ensure that

recovery begins immediately and minimizes any

potential negative impacts on the recovery process.

CPG 101 serves as the foundation for all emergency

planning. Because the process presented in this

guide is an expansion of the CPG 101 process, the

Key Activities for pre-disaster recovery planning

build on the same concepts from response

planning. Examples of similar fundamentals

between the two processes include a community-

based and inclusive planning process; analytical

problem-solving processes; the consideration of

a variety of hazards, risks, and vulnerabilities;

flexibility; and the identification of goals.

Furthermore, effective plans for both response

and recovery delegate responsibility and authority,

and contribute to overall community preparedness

ahead of disasters.

Discussion Point: Differences in

Response and Recovery Planning Goals

A few high-level (and hypothetical) examples of the

fundamental differences in response planning and

recovery planning goals are listed below. Notice

that the goals in response planning are short-term,

whereas the goals in recovery planning are long-term.

Disaster Impact on Local Water Supply

• Potential Response Goal: Deliver emergency water

supply to affected residents.

• Potential Recovery Goal: Address infrastructure or

natural resource impacts to return and enhance

the resiliency of the water supply in the long-term.

Disaster Impact on Local Hospital

• Potential Response Goal: Relocate patients

to other hospitals and establish temporary,

emergency medical care facility.

• Potential Recovery Goal: Establish facilities within

the community, or use regional facilities, to re-

establish a sustainable medical care system.

Disaster Impact on Central Business District

• Potential Response Goal: Inspect and condemn

damaged properties.

• Potential Recovery Goal: Assist small businesses

to resume operations and redevelop a resilient

Central Business District.

Page 22

This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Page 23

V. Linking Pre-Disaster Recovery

Planning and Post-Disaster

Recovery Planning

A variety of steps can be taken before a disaster occurs to plan post-disaster response. Creating a common

understanding of needs and potential challenges, institutional and community disaster awareness, and risks

and vulnerabilities prior to a disaster, all help facilitate the post-disaster recovery process. Additionally,

establishing leadership and outside support (partnerships), reaching consensus on priorities, and

accomplishing other planning activities through a pre-disaster process will benefit the community after a

disaster. If they plan in advance, communities greatly reduce, or in some cases eliminate, the need to address

these activities in the wake of a disaster, and are better prepared to begin timely and efficient management

of impacts and long-term consequences shortly after disaster strikes. Pre-establishing consensus on roles and

responsibilities, leadership, policies, and processes enables the local government, and community at large, to

streamline implementation of the recovery process.

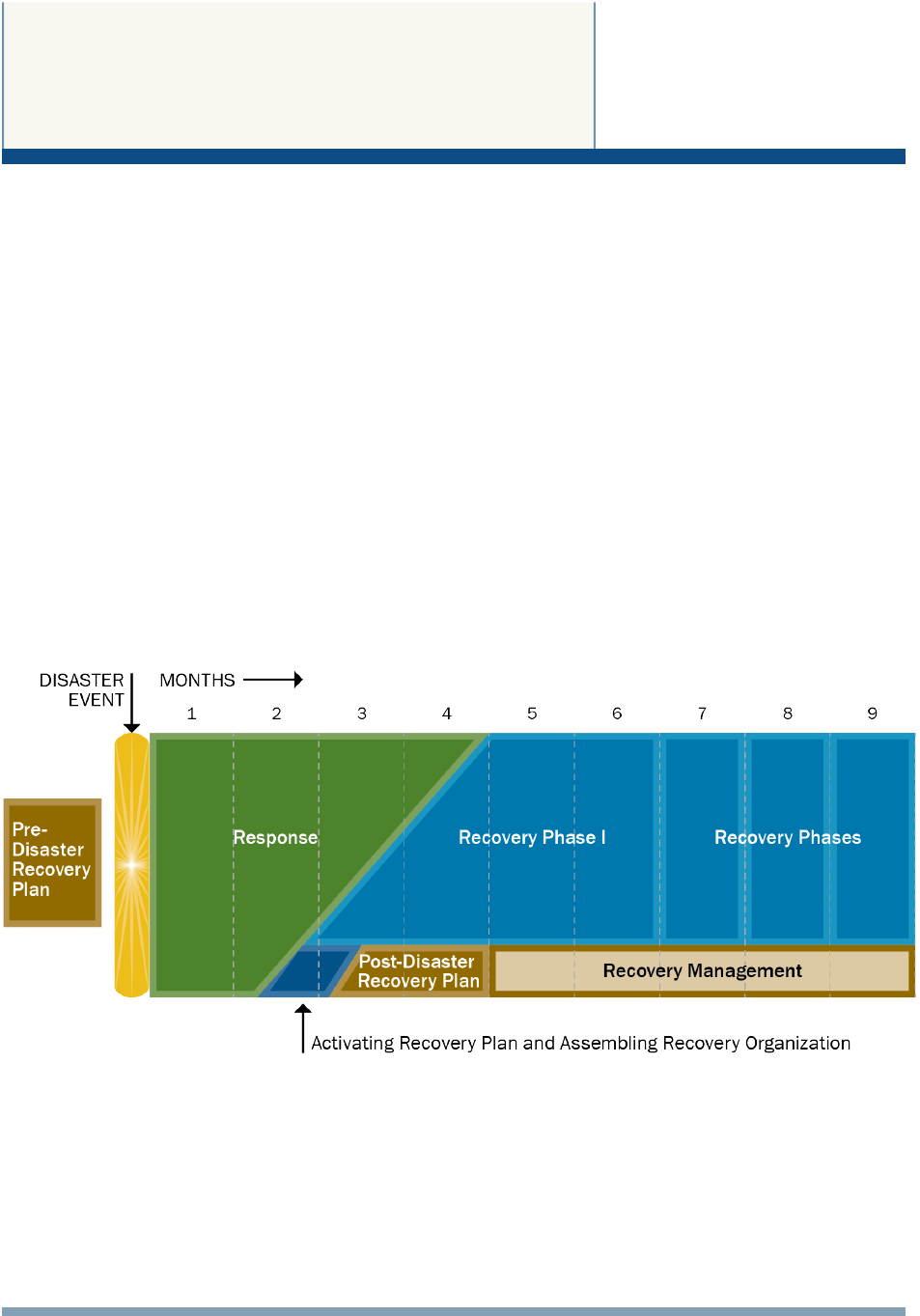

As shown in

Figure 4, the period of organizing for post-disaster recovery and carrying out the post-disaster

recovery planning process must start early as the community transitions to recovery efforts. This period

can be shortened if a pre-disaster plan is in place that defines the steps that are expected to occur, how they

occur, and who will be responsible for them.

Figure 4 Disaster Response and Recovery Timeline

Source: APA, Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery: Next Generation (PAS Report 576) (2015)

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

Page 24

During the planning process, common issues to consider include timeline and transition among functions

and personnel. It is recommended that planners address challenges in early recovery, establish the interface

between response and recovery, and determine when and who will initiate post-disaster recovery planning

and actions. For example, emergency managers and recovery planners often have different perspectives

regarding the appropriate scope of recovery activities, which can lead to coordination conflicts after a

disaster. By involving emergency managers in the pre-disaster planning process, recovery planners can gain a

better understanding of how their methods and goals differ from those of emergency response management,

allowing both processes to operate more smoothly.

Table 1, which is also included in the NDRF, outlines the critical tasks associated with planning for recovery

both pre- and post-disaster. While the process outlined in this guide discusses the tasks associated with all

types of pre-disaster planning activities (i.e., strategic, operational, and tactical planning), it is important to

remember that successful pre-disaster recovery planning will speed post-disaster planning and activities.

Therefore, post-disaster planning tasks are equally important considerations during pre-disaster planning.

For post-disaster planning process guidance, FEMA’s Long-Term Community Recovery Planning Process: A Self-Help Guide

17

describes and discusses a range of critical activities, including assessing needs, assigning leadership, securing

outside support, and reaching consensus. Reviewing the Self-Help Guide to gain a complete understanding of

what a post-disaster planning process entails is highly recommended as preparation for pre-disaster planning

because successful pre-disaster planning prepares a community to act quickly and efficiently and apply a post-

disaster planning process. Critical planning tasks are shown in

Table 1.

17

FEMA, Long-Term Community Recovery Planning Process: A Self Help Guide (2005). http://www.fema.gov/pdf/rebuild/ltrc/selfhelp.pdf.

Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments - FEMA Publication FD 008-03

Page 25

Type of

Planning

Pre-Disaster Post-Disaster

STRATEGIC

Driven by policy,

establishes

planning

priorities

• Develop a mitigation plan that establishes

post-disaster risk reduction priorities and

policies to guide post-disaster recovery and

redevelopment.

• Establish pre-disaster priorities and policies

to guide recovery and reinvestment across the

other Recovery Core Capabilities.

• Develop an inclusive and accessible whole

community public engagement strategy.

• Evaluate current conditions; assess risk,

vulnerability, and potential community-wide

consequences.

• Integrate recovery and mitigation goals and

policies into other Federal, State, regional, and

community plans.

• Establish priorities and identify opportunities

to build resilience, including sustainable

development, equity, community capacity, and

mitigation measures.