AIR TRAFFIC

CONTROL

MODERNIZATION

Progress and

Challenges in

Implementing

NextGen

Report to Congressional Requesters

August 2017

GAO-17-450

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-17-450, a report to

congressional requesters

August 2017

AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL MODERNIZATION

Progress

and Challenges in Implementing

NextGen

What GAO Found

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is implementing the Next Generation

Air Transportation System (NextGen) incrementally and has taken actions to

address challenges to implementation. NextGen has enhanced surface traffic

operations at 39 of the 40 busiest airports in the United States by providing

electronic communications to clear planes for departure, technology that can

expedite clearances and reduce errors. FAA has taken steps to address

challenges such as limited stakeholder inclusion that affected early

implementation of NextGen. For example, FAA established groups of industry

stakeholders and government officials, who worked together to develop

implementation priorities. By 2025, FAA plans to deploy improvements in all

NextGen areas—communications, navigation, surveillance, automation, and

weather. While specific NextGen initiatives and programs have changed over

time, FAA’s 2016 cost estimates for implementing NextGen through 2030 for 1)

FAA and 2) industry—$20.6 and $15.1 billion, respectively—are both within

range of 2007 cost estimates.

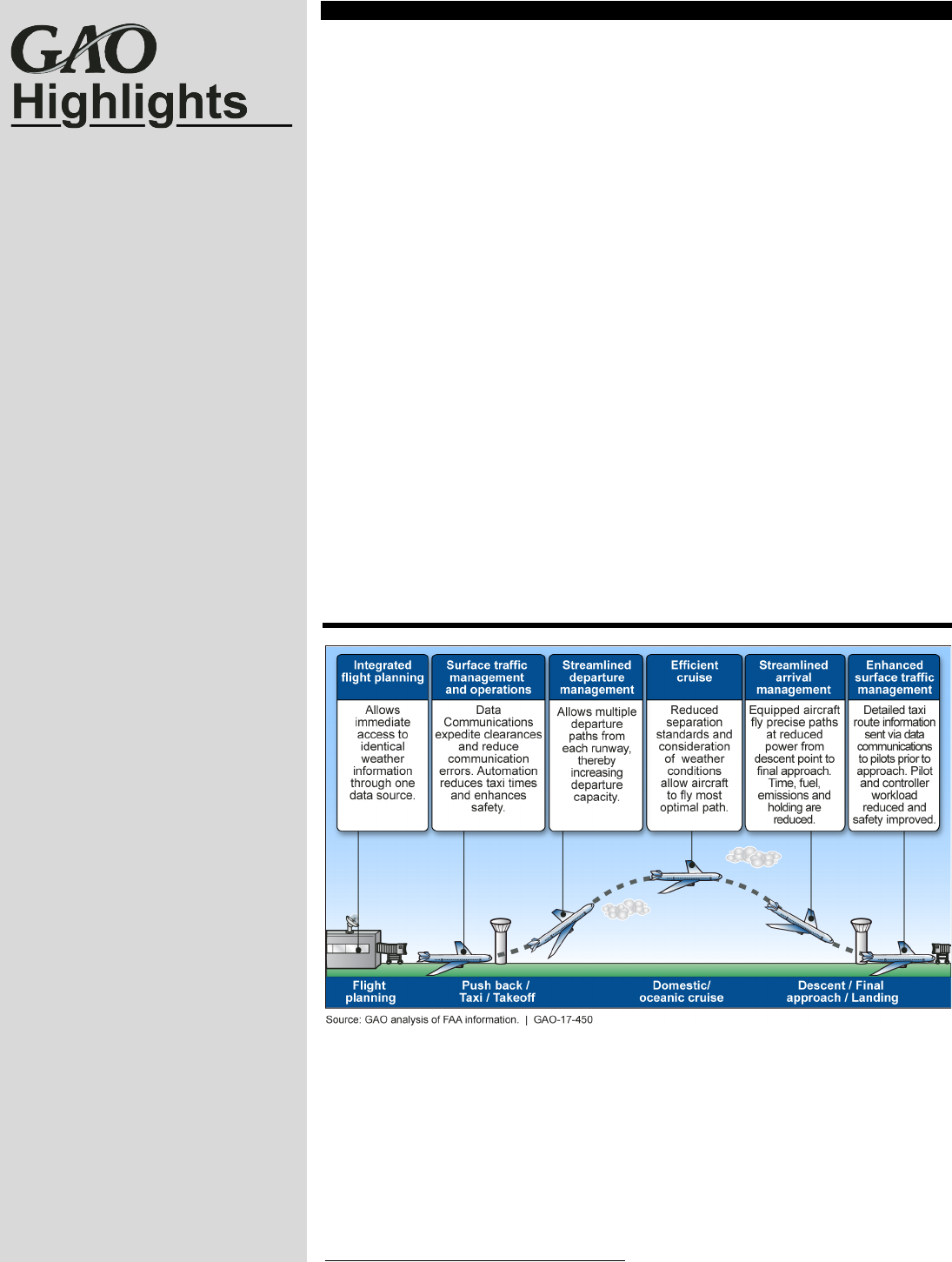

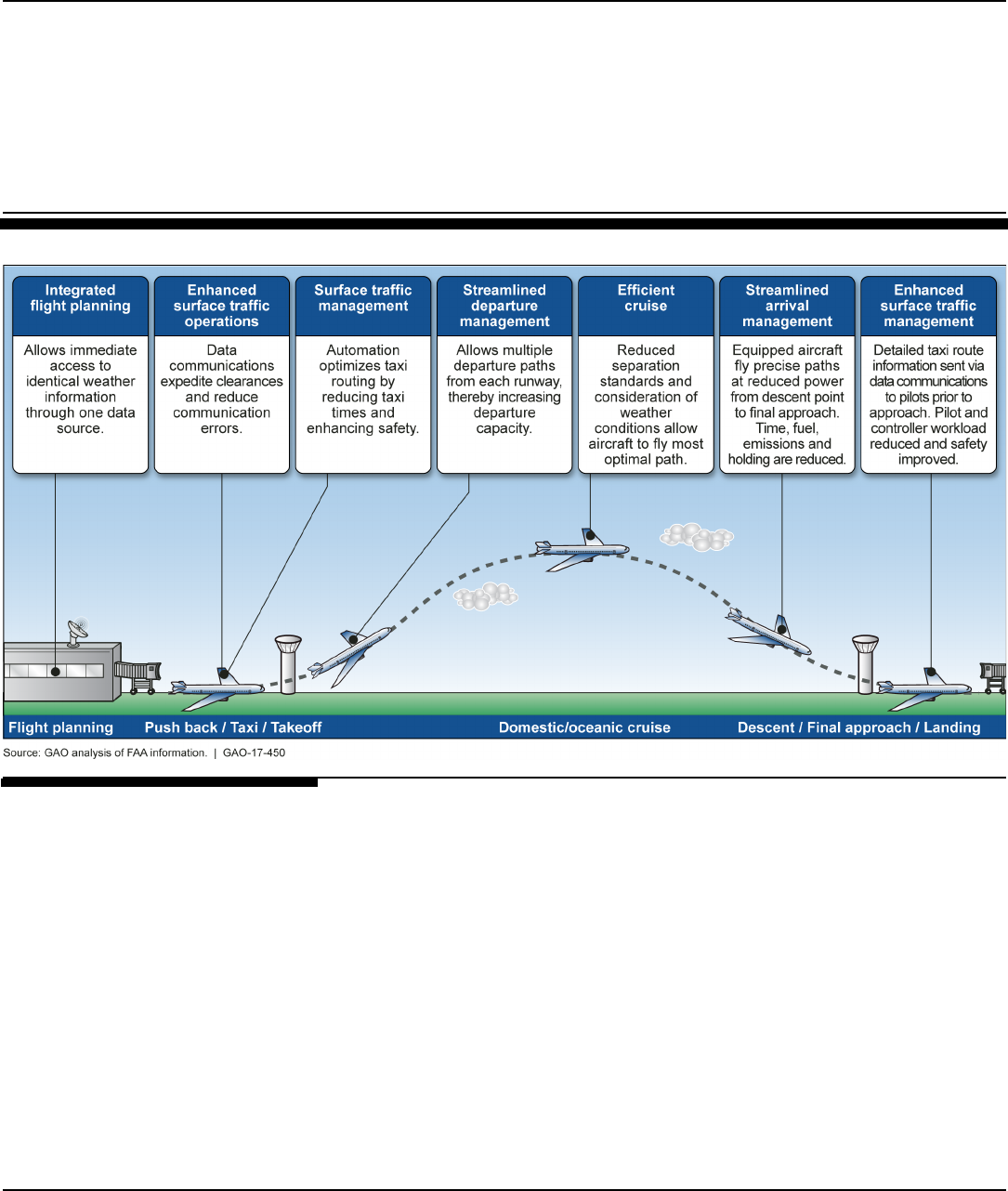

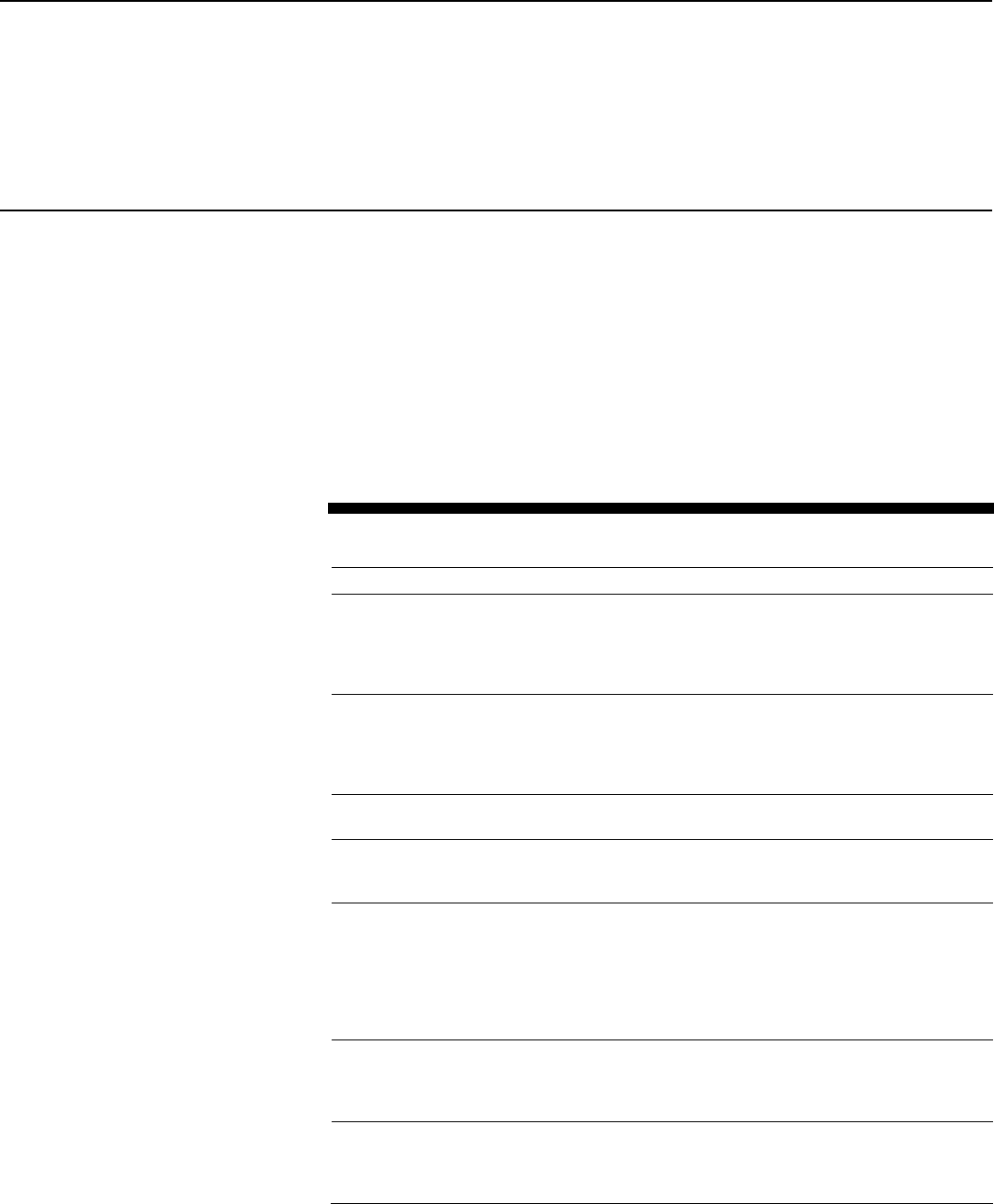

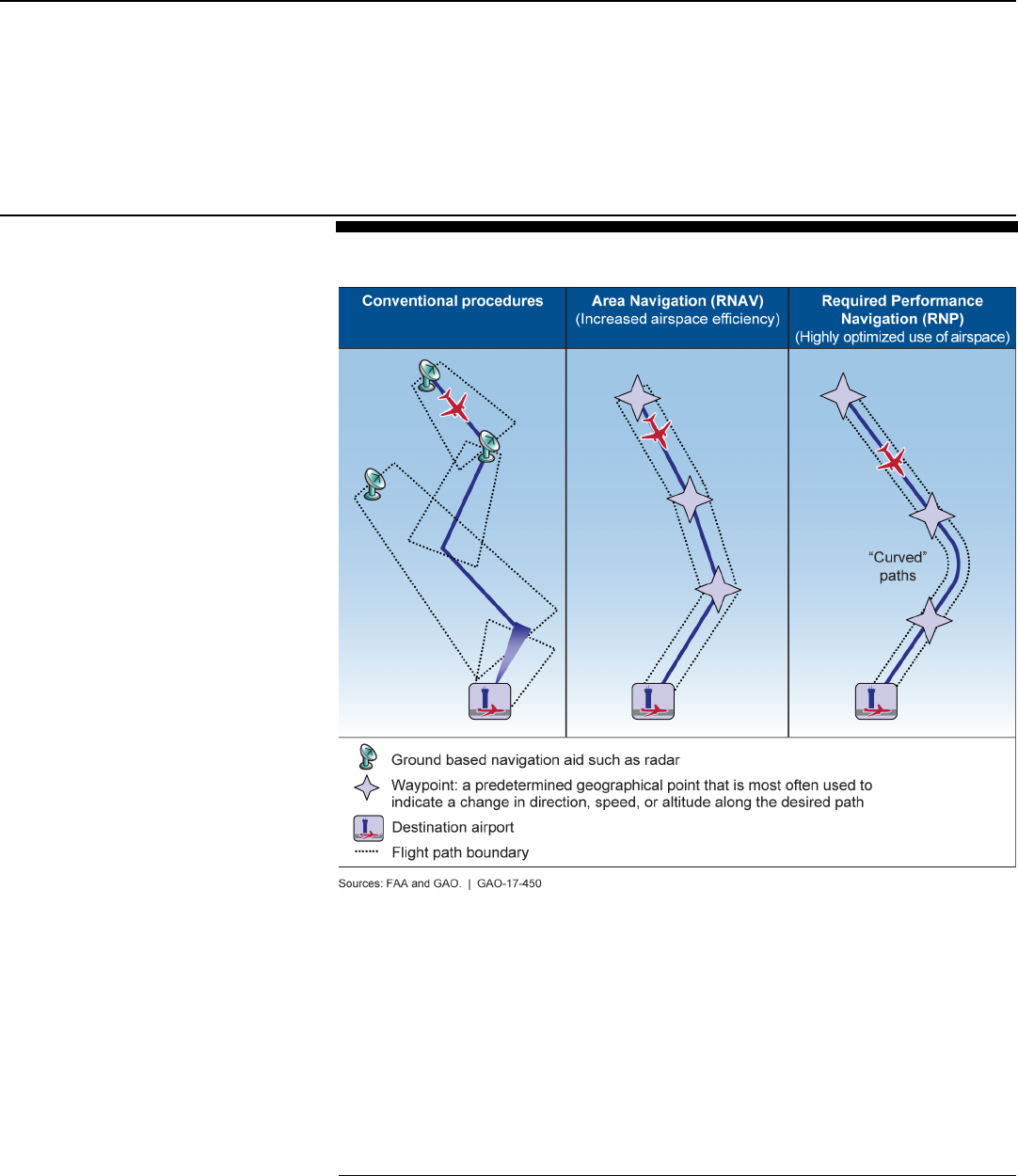

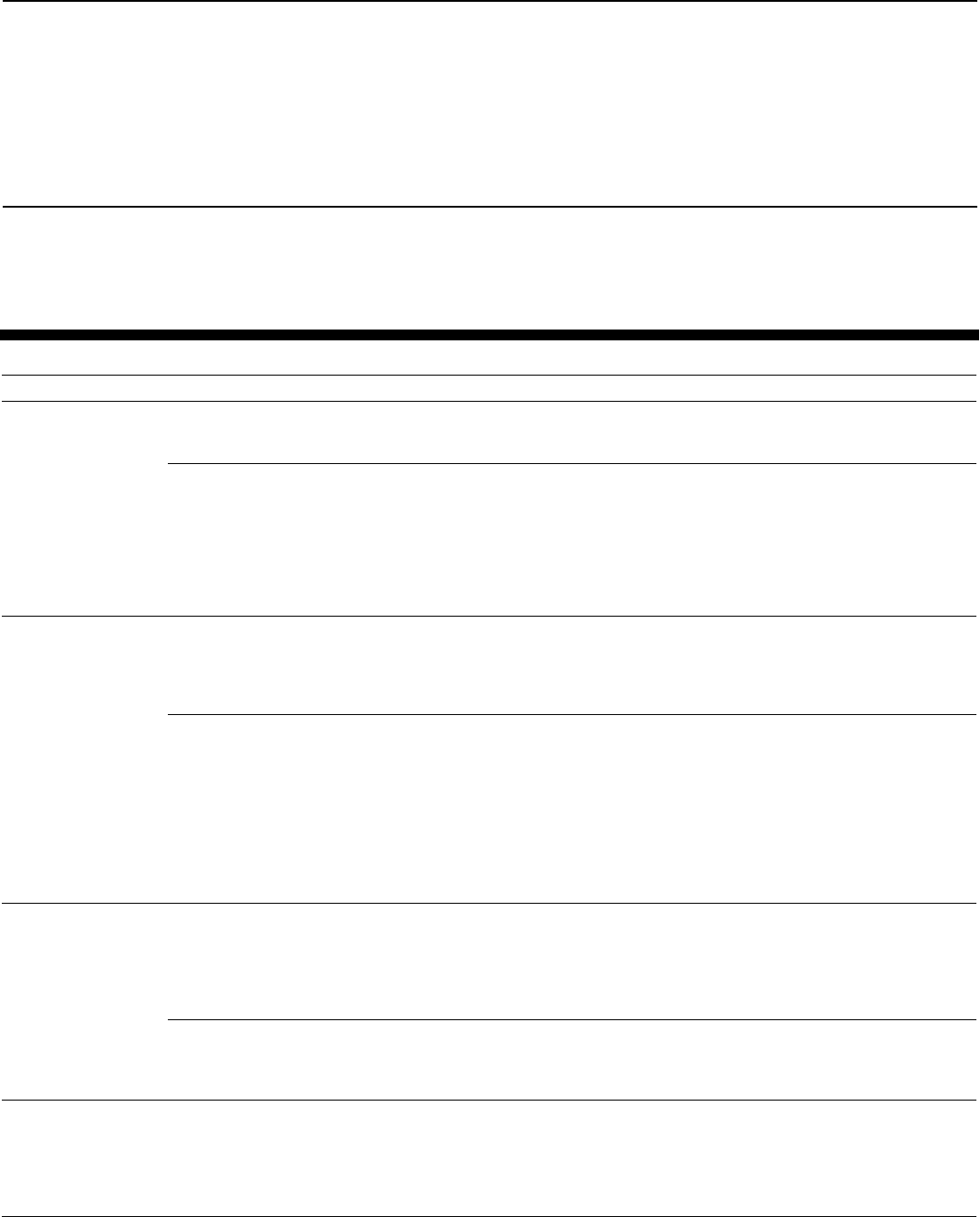

Expected Improvements under the Next Generation Air Transportation System

FAA’s challenges as it continues to implement NextGen include uncertainties

regarding future funding; whether aircraft owners equip their aircraft to use

NextGen improvements; potential air traffic control restructuring; FAA’s

leadership stability; and cybersecurity issues. FAA is taking actions to address

challenges within its control by, for example, prioritizing NextGen improvements

and segmenting them into smaller pieces that each require less funding. While it

is not possible to eliminate all uncertainties, FAA has adopted an enterprise risk

management approach to help it identify and mitigate current and future risks that

could affect NextGen implementation. Moreover, FAA has implemented most of

GAO’s related recommendations.

View GAO-17-450. For more information,

contact Gerald

Dillingham, Ph.D., at (202)

512

-2834 or [email protected].

Why GAO Did This Study

FAA is leading the implementation of

NextGen, which is designed to

transition the nation’s ground-based air

traffic control system to one that uses

satellite navigation, automated position

reporting, and digital communications.

Planning for NextGen began in 2003

and in 2007 the effort was estimated to

cost between $29 and $42 billion by

2025. NextGen is intended to increase

air transportation system capacity,

enhance airspace safety, reduce

delays, save fuel, and reduce adverse

environmental effects from aviation.

Given the cost, complexity, and length

of the project, GAO was asked to

review FAA’s NextGen implementation

efforts. This report examines: 1) how

FAA has implemented NextGen and

addressed implementation challenges;

and 2) the challenges, if any, that

remain for implementing NextGen, and

FAA’s actions to mitigate those

challenges.

GAO reviewed FAA documents,

advisory group reports, and NextGen-

related recommendations made to FAA

by GAO and others. GAO interviewed

a non-generalizable sample of 34 U.S.

aviation industry stakeholders,

including airlines, airports, aviation

experts and research organizations,

among others, to obtain their views on

NextGen challenges and FAA’s efforts

to address them. Stakeholders were

selected based on GAO’s knowledge

of the aviation industry and includes

those that have made NextGen-related

recommendations to FAA, among

other things. GAO also interviewed

FAA officials regarding NextGen

implementation and stakeholders’

views.

Page i GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

Letter 1

Background 3

FAA Is Implementing NextGen Incrementally and Has Taken

Various Actions to Address Challenges 6

FAA Faces Various Challenges to Implementing NextGen 23

Agency Comments 35

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 37

Appendix II Select Planning and Implementation Documents 41

Appendix III Selected Programs in the Next Generation Air Transportation System

(NextGen) 44

Appendix IV Status of NextGen’s Recommendations 48

Appendix V Next Generation Air Transportation System’s (NextGen) Activities

Deferred Until After 2030 51

Appendix VI GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 52

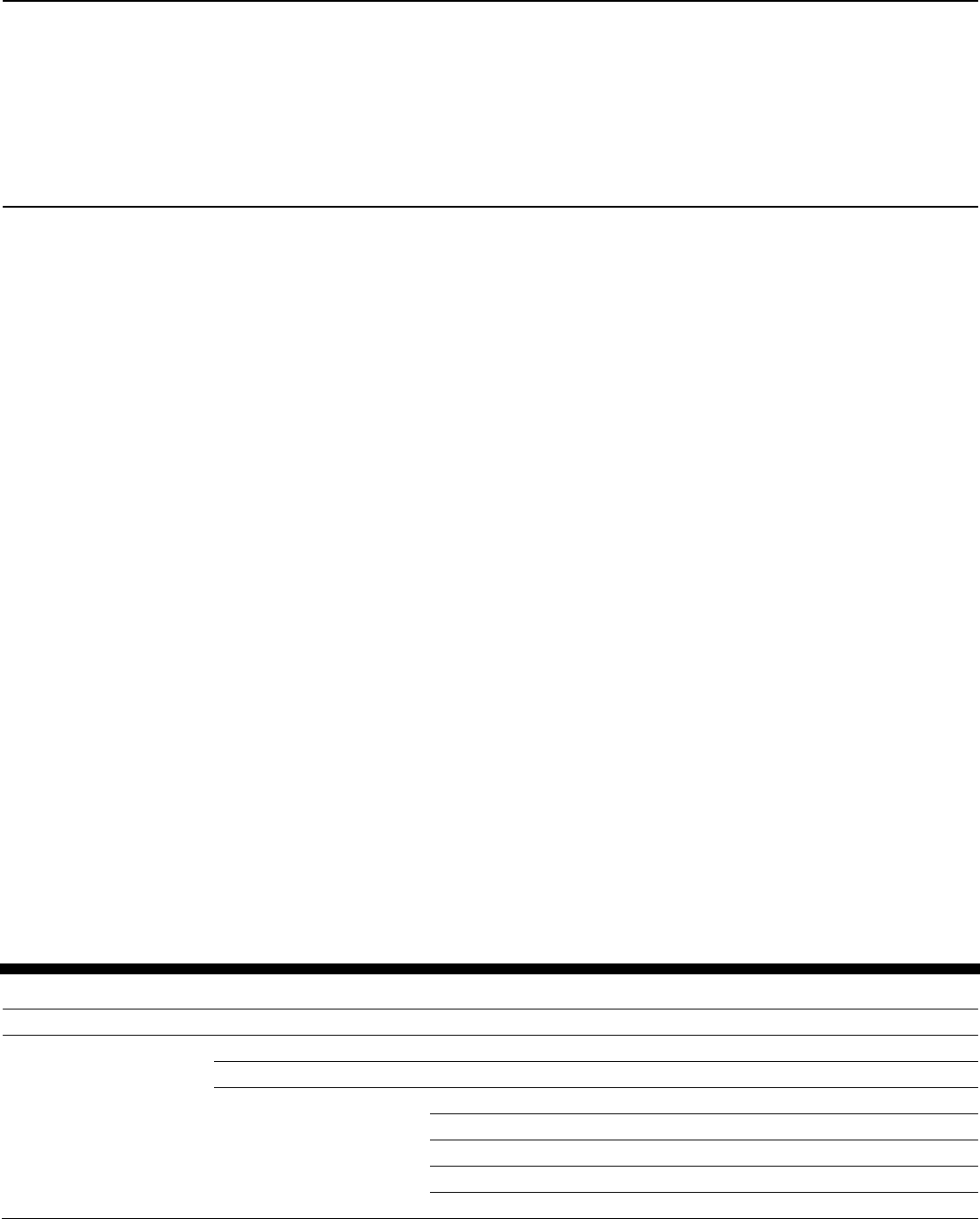

Tables

Table 1: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)’s Portfolios of Next

Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen)

Operational Improvements 9

Table 2: NextGen Mid-Term Implementation Task Force

Recommendation Areas 11

Table 3: List of the 34 Aviation Industry Stakeholders We

Interviewed 38

Table 4: Select Planning and Implementation Documents for the

Next Generation Air Transportation System, 2004-2016 41

Contents

Page ii GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

Table 5: Selected Programs in the Next Generation Air

Transportation System (NextGen) 44

Table 6: Next Generation Air Transportation System’s (NextGen)

Activities Deferred Until After 2030 51

Figures

Figure 1: Improvements to Phases of Flight Expected under the

Next Generation Air Transportation System 6

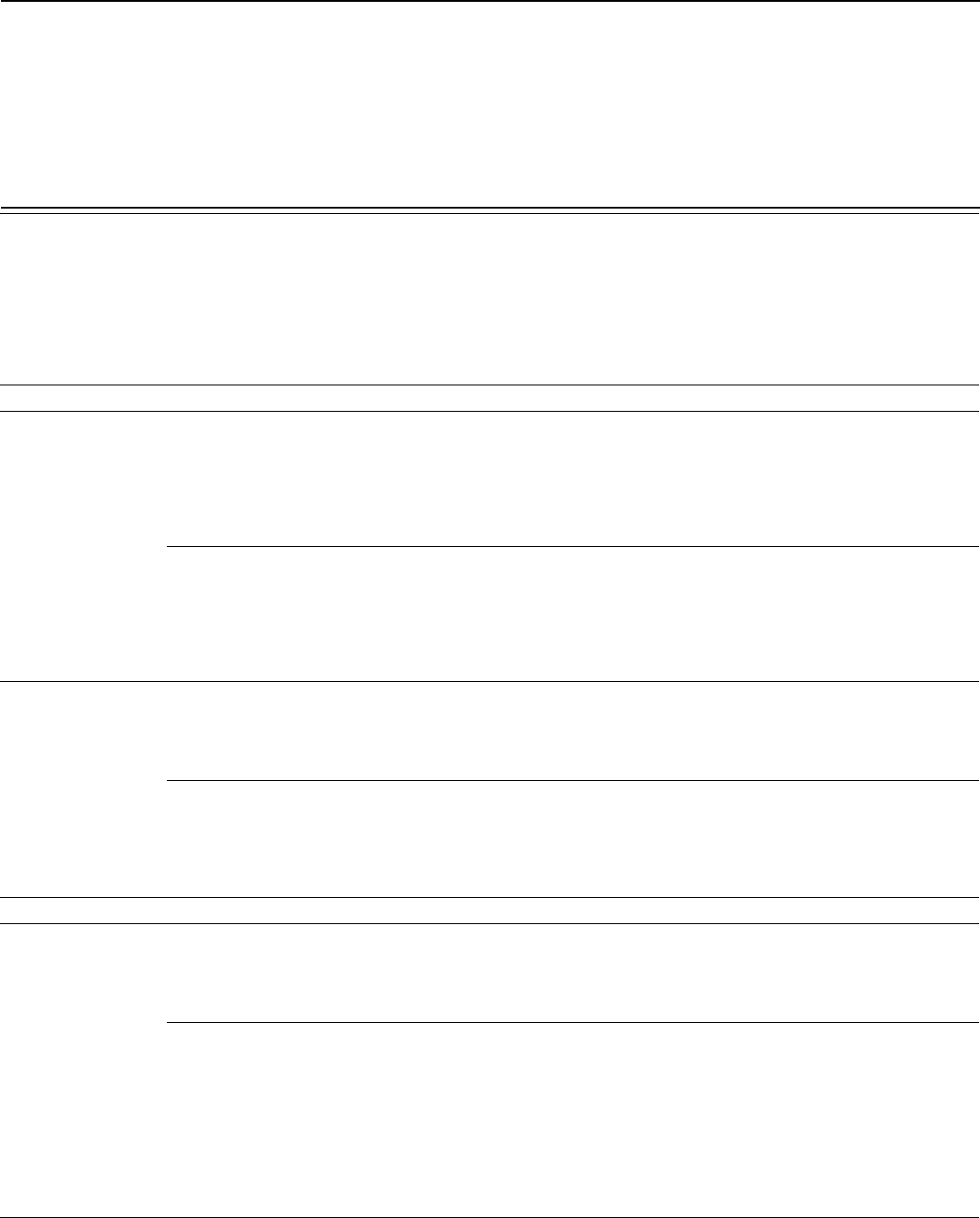

Figure 2: Metroplex Sites and Their Completion Status, as of

March 2017 13

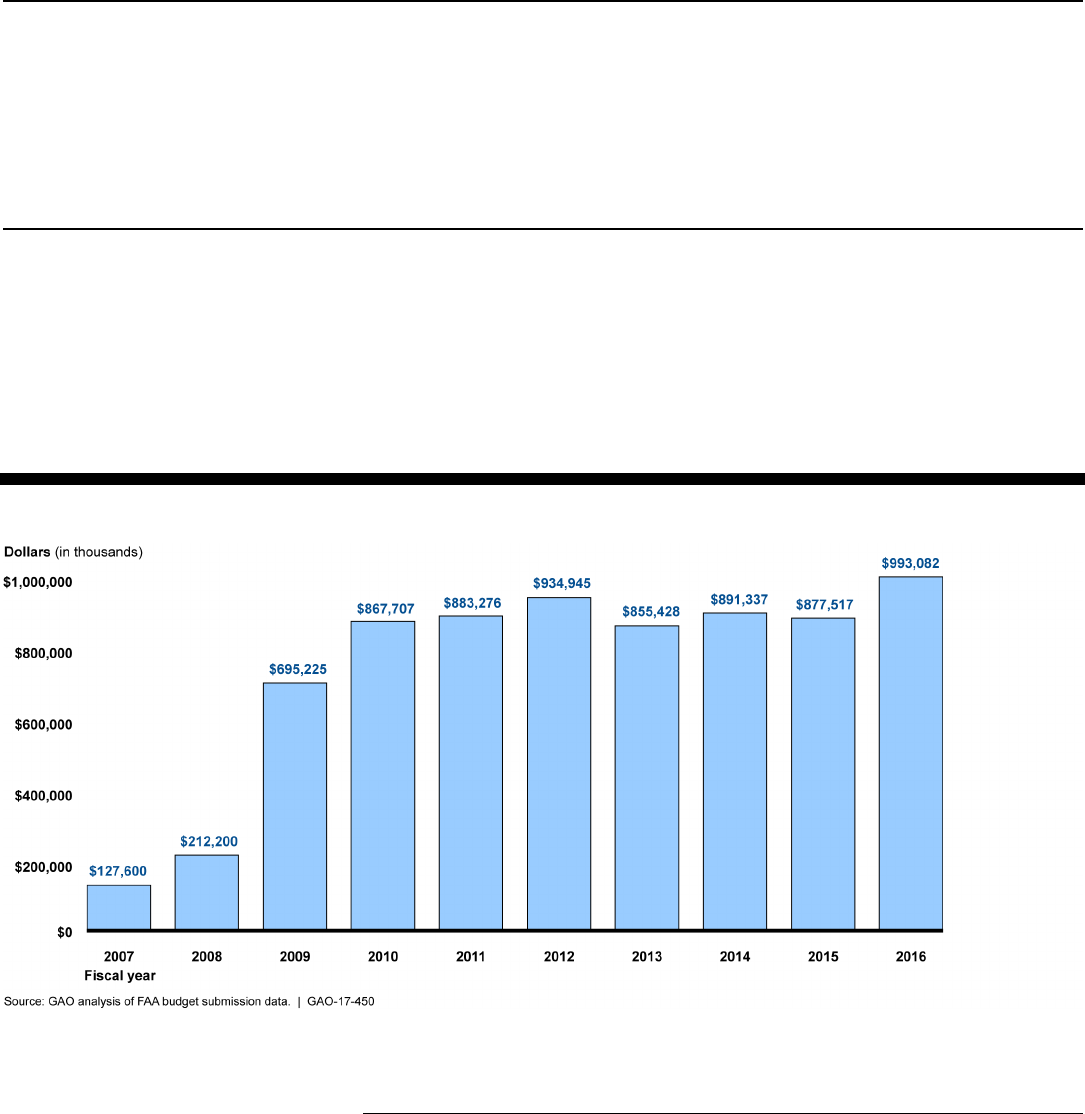

Figure 3: Federal Funds the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

Has Received for Next Generation Air Transportation

System (NextGen) Programs and Activities, Fiscal Years

2007 through 2016 22

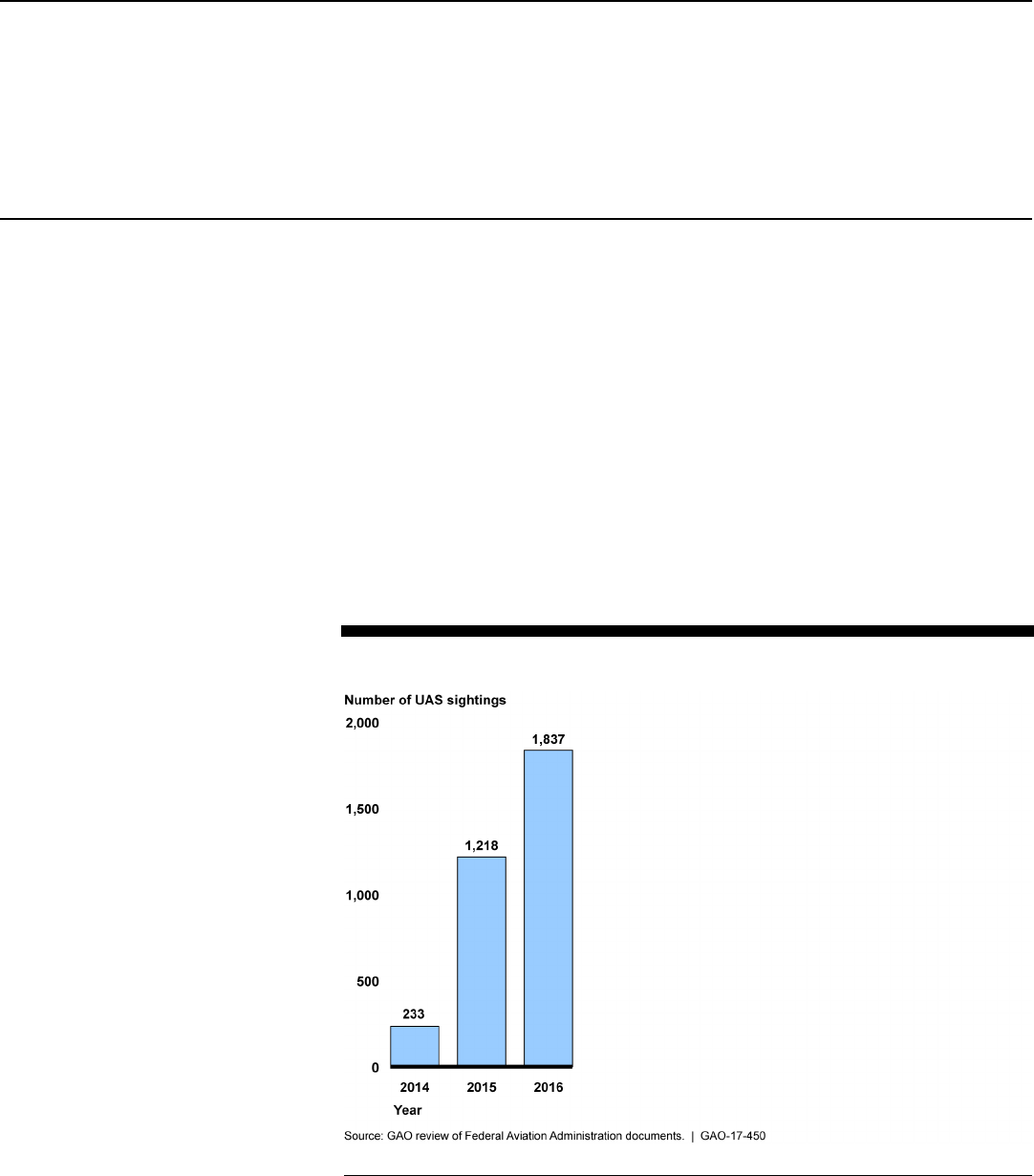

Figure 4: The Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) Annual

Unmanned Aircraft Systems Sightings, 2014 through

2016 30

Figure 5: Procedures Using Conventional Equipment and

Performance-Based Navigation Technologies 32

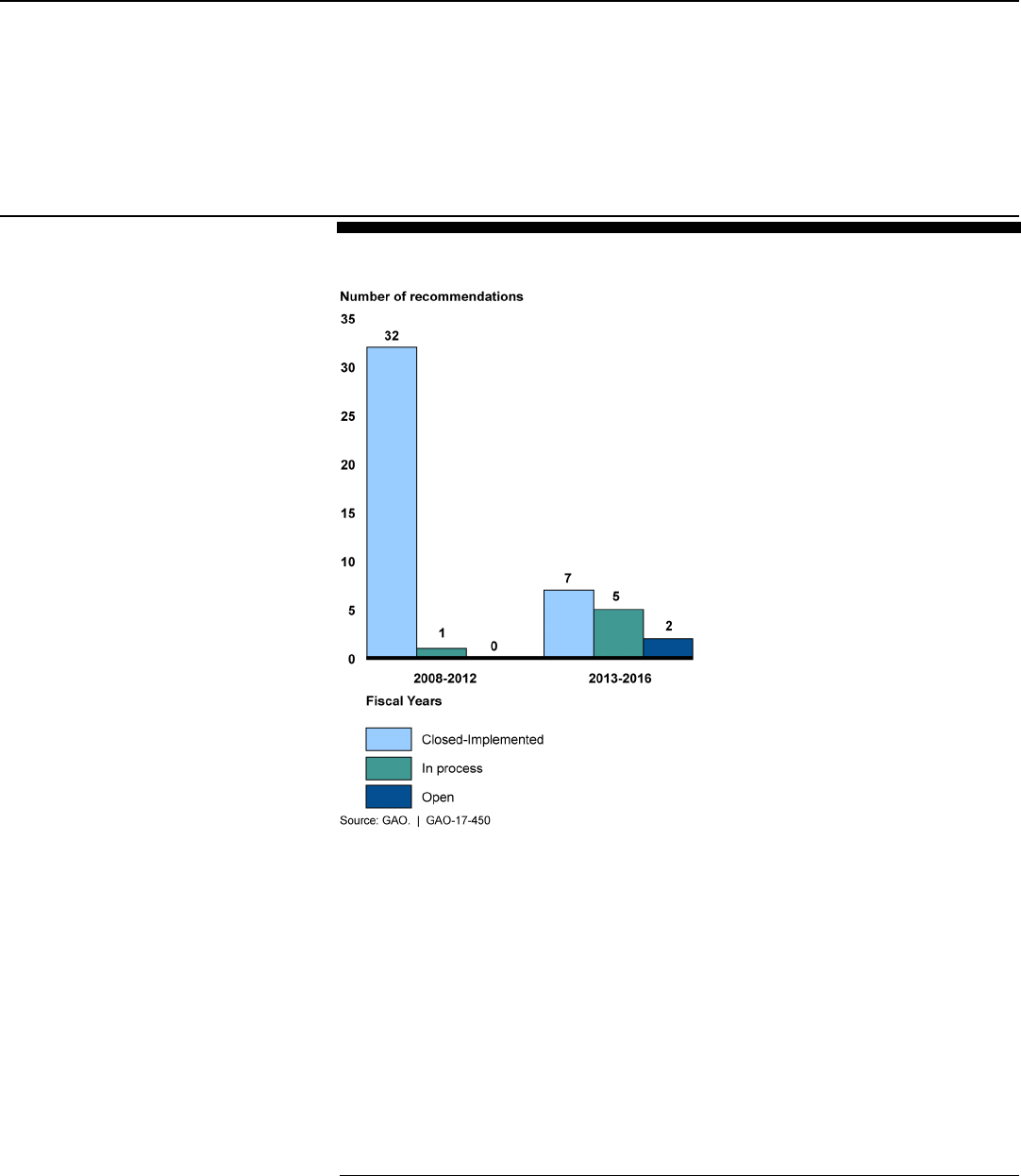

Figure 6: Status of GAO NextGen-Related Recommendations

Made to FAA, Fiscal Years 2008–2016 49

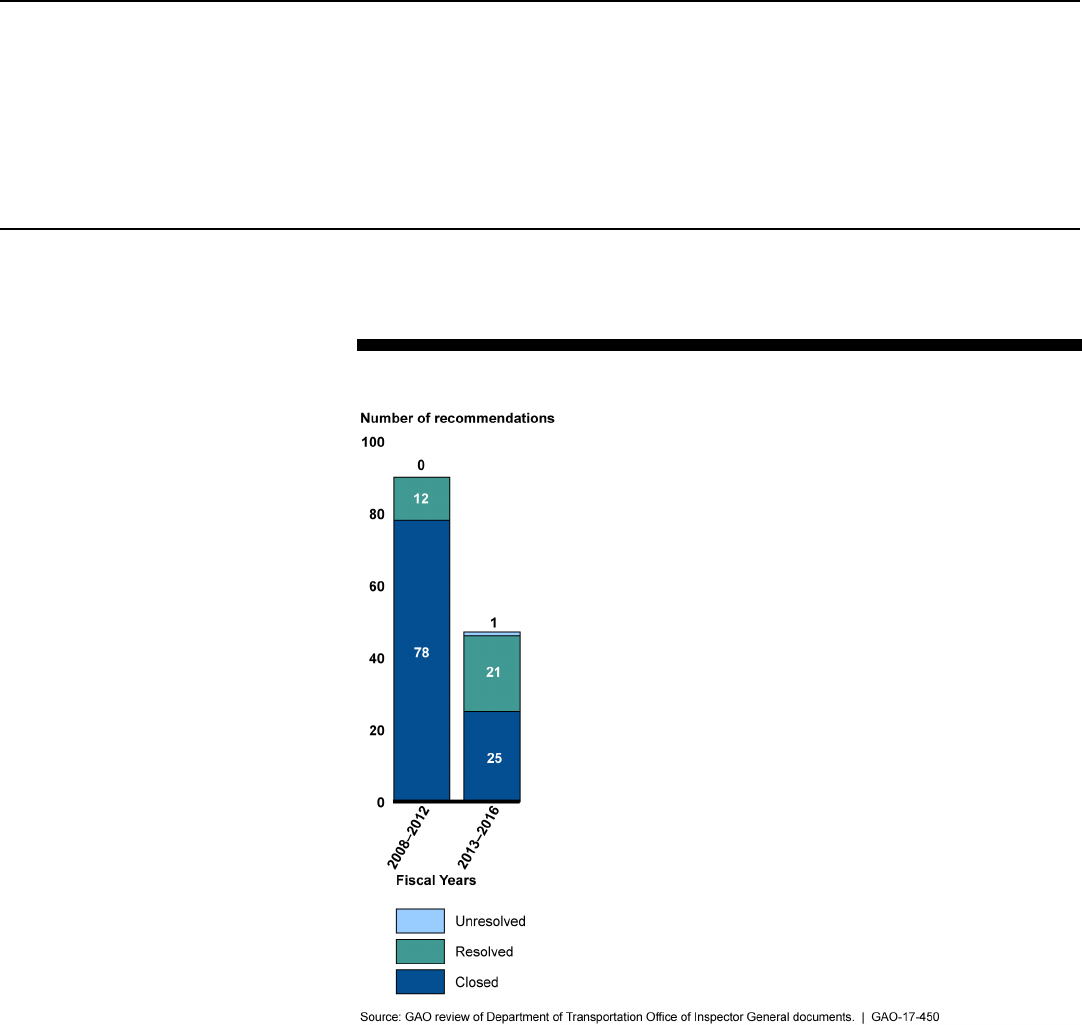

Figure 7: Status of Department of Transportation Office of

Inspector General’s NextGen Recommendations Made to

FAA, Fiscal Years (FY) 2008–2016 50

Abbreviations

ADS-B Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast

AIMM Aeronautical Information Management Modernization

ATC air traffic control

ATN Aeronautical Telecommunications Network

ATO Air Traffic Organization

Page iii GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

AVS Office of Aviation Safety

CATM-T Collaborative Air Traffic Management-Technologies

CSS-Wx Common Support Services-Weather

CIO Chief Information Officer

DAC Drone Advisory Committee

Data Comm Data Communications

DOT Department of Transportation

DOT OIG Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

F&E facilities and equipment

ERAM En Route Automation Modernization

ERM Enterprise Risk Management

GPS Global Positioning System

JPDO Joint Planning and Development Organization

NAC NextGen Advisory Committee

NAS National Airspace System

NextGen Next Generation Air Transportation System

NPS NextGen Performance Snapshots

NVS National Airspace System Voice System

NWP NextGen Weather Processor

OIG Office of Inspector General

OMB Office of Management and Budget

PBN Performance-Based Navigation

RE&D research, engineering and development

RTCA formerly known as the Radio Technical Commission for

Aeronautics

SOA Service Oriented Architecture

SWIM System Wide Information Management

TAMR Terminal Automation Modernization and Replacement

TBFM Time Based Flow Management

TFDM Terminal Flight Data Manager

TMA Traffic Management Advisor

UAS unmanned aircraft systems

Wake Recat Wake Turbulence Re-Categorization

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

August 31, 2017

The Honorable Bill Shuster

Chairman

The Honorable Peter DeFazio

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The Honorable Frank LoBiondo

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Aviation

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The U.S. National Airspace System (NAS) handles nearly 70,000 flights a

day and is generally considered the safest, busiest and most complex

airspace system in the world.

1

Key aviation stakeholders—the Federal

Aviation Administration (FAA), airlines, airports, general aviation,

business aviation, aircraft manufacturers, and aviation professionals—

work together to ensure these results. As part of this effort, FAA is leading

the development of the Next Generation Air Transportation System

(NextGen), a complex, long-term initiative that will transition the current

ground-based radar air-traffic control system to a system based on

satellite navigation, automated position reporting, and digital

communications. NextGen is intended to, among other things, increase

air transportation system capacity, enhance airspace safety, reduce

delays experienced by airlines and passengers, save fuel, and reduce

adverse environmental impacts from aviation. Full implementation of

NextGen requires investment by the federal government through FAA, as

well as by airlines in new technologies and the development of new

policies and procedures.

1

The National Airspace System is a shared network of U.S. airspace; air navigation

facilities, equipment, and services; airports or landing areas; aeronautical charts,

information, and services; rules, regulations, and procedures; technical information; and

manpower and material.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

In December 2003, Congress passed the Vision 100—Century of Aviation

Reauthorization Act, which created the Joint Planning and Development

Organization (JPDO) within FAA to plan for and coordinate an

interagency effort to transition to NextGen by 2025.

2

However, FAA has

been largely responsible for implementing the policies and systems

necessary for NextGen to become operational. In 2014, with NextGen

implementation underway, Congress ended funding for JPDO, and FAA’s

Interagency Planning Office assumed lead responsibilities for

coordinating FAA’s NextGen implementation with other agencies.

3

We have monitored and reported on NextGen since its inception.

4

After

more than a decade of planning and implementation, you asked us to

review the status of FAA’s NextGen implementation efforts. This report

examines: (1) how FAA has implemented NextGen and addressed

implementation challenges; and (2) the challenges, if any, that remain for

implementing NextGen, and FAA’s actions to mitigate those challenges.

To address these objectives, we reviewed FAA planning documents for

NextGen and FAA reports and briefings related to ongoing NextGen

efforts. We also assessed current cost estimates for implementing

NextGen through 2030 and compared them to 2007 estimates from

JPDO. We reviewed reports and NextGen-related recommendations

issued by GAO, the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Office of

Inspector General (DOT OIG), and NextGen advisory groups; and

assessed FAA’s efforts to address these recommendations. We

interviewed FAA officials with a role in implementing NextGen, including

2

FAA’s partner agencies in the JPDO included the Department of Transportation, the

Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of

Commerce, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the Office of Science

and Technology Policy in the Executive Office of the President. Vision 100—Century of

Aviation Reauthorization Act, Pub. L. No. 108-176, §§ 709-710, 117 Stat. 2490, 2582

(2003).

3

The Interagency Planning Office is located within the Office of NextGen and coordinates

with agencies such as the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security.

4

See, for example, GAO, National Airspace System: Transformation Will Require Cultural

Change, Balanced Funding Priorities, and Use of All Available Management Tools,

GAO-06-154 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 14, 2005); GAO, NextGen Air Transportation

System: FAA’s Metrics Can Be Used to Report on Status of Individual Programs, but Not

of Overall NextGen Implementation or Outcomes, GAO-10-629 (Washington, D.C.: July

27, 2010); GAO, Next Generation Air Transportation System: Improved Risk Analysis

Could Strengthen Global Interoperability Efforts, GAO-15-608 (Washington, D.C.: July 29,

2015).

Page 3 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

officials within the NextGen Office and its Interagency Planning Office, the

Office of Aviation Safety (AVS), and the Air Traffic Organization (ATO).

To obtain a diverse set of views, we also interviewed 34 stakeholders

using open-ended questions to obtain their perspectives on efforts FAA

has made to address challenges that have affected NextGen

implementation. These 34 stakeholders consisted of a non-probability

sample of aviation experts and officials from airlines, airports, former FAA

officials, research and development organizations, general aviation

associations, labor unions and professional associations, and

manufacturers and service providers. We created an initial list of

stakeholders using internal knowledge of the aviation industry. We further

developed the list of stakeholders by reviewing NextGen-related literature

and identifying industry stakeholders that have made NextGen-related

recommendations to FAA. To determine the common themes that we are

reporting on, we conducted a content analysis of the interviewees’

responses. The results of our interviews are not generalizable to all

industry stakeholders. For more information on our scope and

methodology, including a listing of FAA divisions and industry

stakeholders we interviewed, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2015 to August

2017 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

FAA has pursued several different modernization efforts for air traffic

control (ATC) since FAA’s creation by the Federal Aviation Act of 1958.

5

These efforts to upgrade the air-traffic control system included the

installation of a semi-automated air-traffic control system beginning in the

mid-1960s and an air traffic control modernization program beginning in

5

Federal Aviation Act of 1958, Pub. L. No. 85-726, § 301, 72 Stat. 731, 744 (1958). In

1966, the previously independent Federal Aviation Agency that the Act created was

renamed the Federal Aviation Administration and made part of the new Department of

Transportation. Pub. L. No. 89-670, § 3(e)(1), 80 Stat. 931, 932 (1966).

Background

FAA’s Early Modernization

Efforts for Air Traffic

Control

Page 4 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

1981. The 1981 modernization program was intended to replace and

upgrade the equipment and facilities of the NAS to meet an expected

increase in traffic volume, enhance the margin of air safety, and increase

the efficiency of the air-traffic control system. The centerpiece of the

program was the Advanced Automation System, which would replace

computer hardware and software and controller work stations at tower,

terminal, and en-route facilities.

FAA restructured the automation program in 1994 after the estimated cost

to deploy it had tripled, capabilities were shown to be significantly less

than promised, and delays were expected to run nearly a decade.

6

In

1995, we placed FAA’s air traffic control modernization efforts on our

watch list of high-risk federal programs due to the cost, complexity,

criticality to FAA’s mission, and problematic history.

7

By 2003, the

estimated cost of FAA’s air-traffic control modernization efforts had grown

from $12 billion to $51 billion.

In the early 2000s, the U.S airspace system was experiencing significant

congestion and delays, with about one in every four flights delayed.

Additionally, forecasts called for a possible tripling of air traffic by 2025,

which raised concerns about the air-traffic control system’s ability to

handle demand. In December 2003, Congress passed the Vision 100—

Century of Aviation Reauthorization Act, which created the JPDO within

FAA to plan for and coordinate a transition to NextGen by 2025.

8

Congress’s goals for NextGen were to improve the level of safety,

security, efficiency, quality, and affordability of the NAS and aviation

services; take advantage of data from emerging technologies and

integrate data streams from multiple sources; and accommodate and

encourage substantial growth in domestic and international

transportation, among other things. Congress assigned the JPDO the

6

This restructuring included cancelling segments of the initial automation program, scaling

back others, and ordering the development of less costly alternatives. Three of five

segments of the Advanced Automation System were cancelled, one segment was scaled

back, and another segment was unaffected.

7

GAO removed FAA’s air traffic control modernization efforts from the high-risk list in 2009

because of its progress in addressing most of the root causes of its past problems and its

commitment to sustaining progress in the future. GAO, High Risk Series: An Update,

GAO-09-271 (Washington, D.C.: January 2009).

8

Vision 100—Century of Aviation Reauthorization Act, Pub. L. No. 108-176, §§ 709-710,

117 Stat. 2490, 2582 (2003).

NextGen

Page 5 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

responsibility to develop an integrated plan for NextGen and facilitate

collaboration between FAA and other federal agencies on NextGen

efforts. Since passage of the Vision 100 Act, NextGen has evolved from a

high-level vision developed by the JPDO to detailed plans currently being

implemented by FAA.

9

See appendix II for more detail on FAA’s planning

and implementation documents for NextGen.

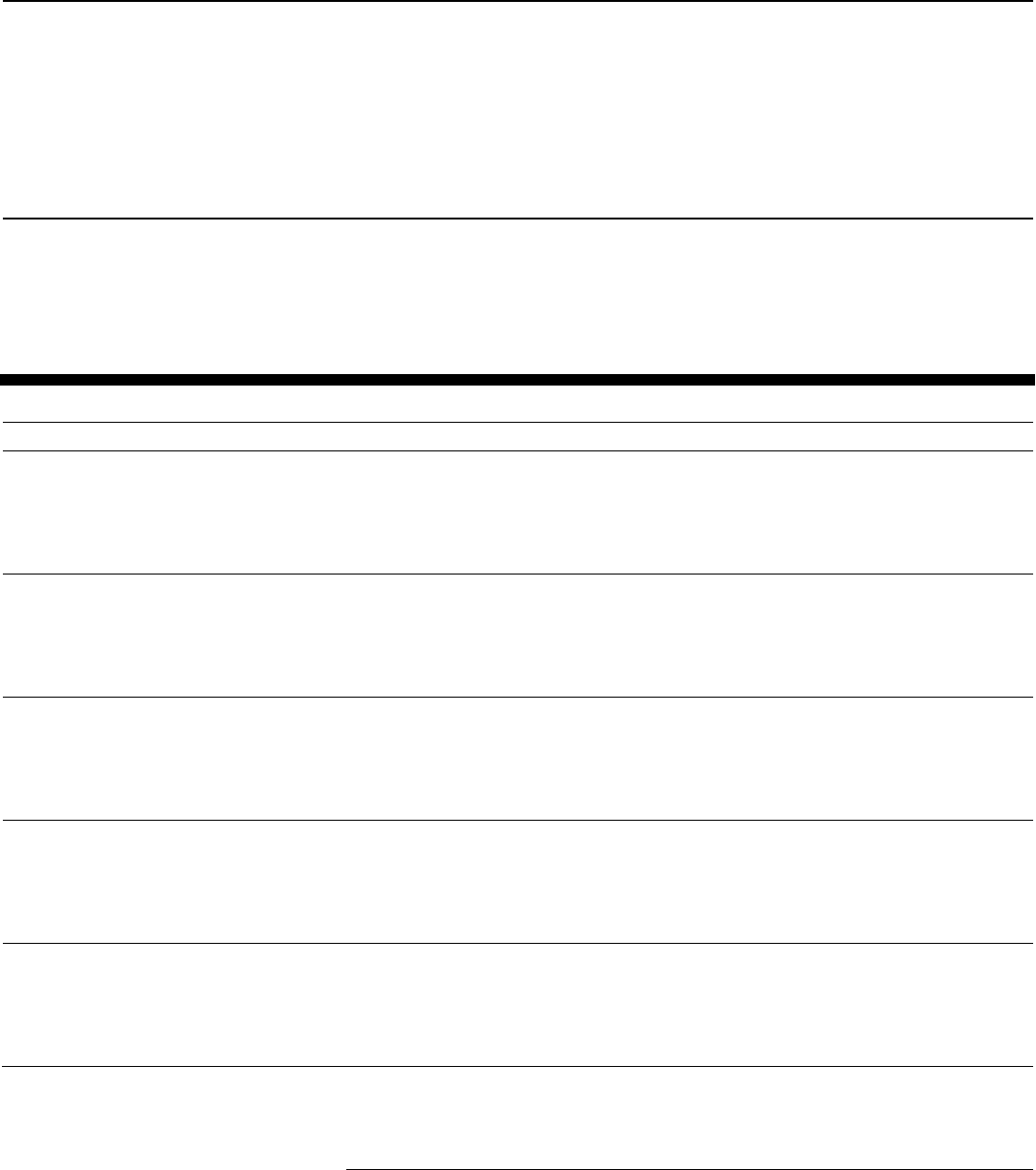

NextGen is a system of systems designed to improve operations in all

phases of a flight, through the replacement of the legacy radar-based air

traffic control system with a satellite-based system that includes digital

communications, among other improvements. NextGen includes a variety

of programs that deliver specific improvements to the NAS. See figure 1

below for some of the improvements to the phases of flight that NextGen

is expected to deliver. For example, under enhanced-surface-traffic

operations, a service provided by FAA’s Data Communications program

allows an air traffic controller to send flight-departure clearance

instructions to aircraft electronically, which can expedite clearances and

reduce communication errors. Under an improvement to streamline arrival

management, performance-based navigation allows aircraft equipped

with appropriate technology to fly precise paths at reduced power, which

saves time, conserves fuel, and reduces exhaust emissions. In addition,

FAA is deploying some programs that are necessary to implement

NextGen programs. For example, the En Route Automation

Modernization (ERAM) program replaced the computer system used by

air traffic controllers at en route centers, a step that was necessary to

deploy some NextGen programs.

10

9

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2014 did not include funding for the JPDO,

resulting in its closure. Pub. L. No. 113-76, 128 Stat. 5 (2014). FAA has created an

Interagency Planning Office within FAA to replace certain functions of the JPDO and

coordinate federal investment in NextGen across agencies.

10

En route centers are air traffic control facilities responsible for guiding aircraft as they

travel between airports.

Page 6 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

Figure 1: Improvements to Phases of Flight Expected under the Next Generation Air Transportation System

FAA is implementing NextGen incrementally through six NextGen-related

areas—communications, automation, navigation, surveillance, weather,

and foundational programs. FAA has faced challenges in including

stakeholders and in measuring and reporting on NextGen progress. In

response, FAA has encouraged the formation of groups of stakeholders

to advise it on implementing NextGen and measuring its progress, and

has worked to incorporate industry preferences into its implementation of

NextGen. For example, FAA is deploying new navigation procedures in

“metroplexes”— geographic areas covering several airports that serve

major metropolitan areas—following a recommendation from a

government and industry task force. FAA has also developed a website

that reports on outcome-based performance metrics for NextGen. FAA

plans to implement the concepts that will transform the NAS to a NextGen

system by 2025, and current total cost estimates for NextGen are within

the JPDO’s 2007 estimates.

In the late 1990s, building on lessons learned from previous air traffic

control modernization efforts and recommendations from stakeholders,

FAA Is Implementing

NextGen

Incrementally and

Has Taken Various

Actions to Address

Challenges

Strategy for Implementing

NextGen

Page 7 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

FAA shifted its strategy for air traffic control modernization. In contrast to

previous modernization efforts, in which FAA sought to build highly

complex software-intensive systems all at once, FAA adopted a phased

approach to modernization that allowed FAA to make mid-course

corrections and avoid costly late-stage changes. JPDO later adopted this

approach for developing and refining its enterprise architecture—a

technical description of the NextGen system that was designed to provide

a common tool for planning the complex, interrelated systems that would

make up NextGen. According to FAA officials we interviewed, the

development and implementation of NextGen is an iterative and

evolutionary process. However, some stakeholders told us that FAA had

originally described NextGen as a transformative initiative. A report from a

2015 National Academy of Sciences study commented that NextGen

meant different things to different people, from a wide-ranging

transformational vision to a much more concrete set of phased

incremental changes to various parts of the NAS, and recommended

resetting expectations. The study committee concluded that NextGen

today is primarily an incremental modernization effort.

The report also

noted that given the continuing rapid pace of technological evolution and

ongoing changes in what is demanded of the NAS, the NextGen effort is

properly seen as an ongoing process, punctuated by particular efforts

focused on particular capabilities.

11

According to FAA officials, NextGen

can be both incremental and result in a transformation.

FAA has begun developing and deploying elements of many NextGen

communications, automation, navigation, surveillance, and weather

programs, as well as foundational programs on which NextGen

improvements depend. A short overview of these six NextGen-related

program areas can be found below. See appendix III for further

information about select NextGen programs.

• Foundational programs to provide the infrastructure necessary to

deploy NextGen programs. For example, the Terminal Automation

Modernization and Replacement (TAMR) program includes updates to

air traffic control systems to help controllers manage air traffic.

• Communications programs to enhance communication and

information sharing in the NAS. This area includes programs such as

Data Communications, which will supplement the voice

11

National Research Council, A Review of the Next Generation Air Transportation System:

Implications and Importance of System Architecture (Washington, DC: 2015).

Page 8 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

communications currently used to relay information between air traffic

controllers and aircraft with pre-scripted email-like messages.

• Navigation programs that use more efficient routes and procedures to

save fuel, reduce flight times, increase traffic flow and capacity, and

reduce exhaust emissions. This area includes programs such as

Performance-Based Navigation (PBN), which provides new, more

efficient aircraft flight routes and procedures that primarily use

satellite-based navigation.

• Surveillance programs to provide more precise tracking of aircraft,

vehicles, and other objects to air traffic controllers and pilots. This

area includes programs such as Automatic Dependent Surveillance-

Broadcast (ADS-B), which uses Global Positioning System (GPS)

satellites to determine an aircraft’s location, speed, and other data.

• Automation programs to enhance air traffic control efficiency, reduce

costs, and provide traffic flow management solutions. This area

includes programs such as Time Based Flow Management, which is

designed to optimize the flow of aircraft as they arrive in or depart

from congested airspace and airports.

• Weather programs to manage and disseminate weather information,

help identify safety hazards, and provide support for strategic traffic

flow management.

12

This area includes programs such as Common

Support Services-Weather, which will enable access to standardized

weather information.

Some NextGen improvements have already been deployed. For example,

Data Communications departure clearance services have been deployed

at 55 airports—all of the locations for the first phase of the Data

Communications program, including 39 of the 40 busiest commercial

airports in the United States.

13

FAA has segmented the implementation of

some of its NextGen programs into time frames during which FAA will

implement certain portions of the programs. By segmenting

implementation, FAA divides each program into defined parts that require

less funding than the entire program.

12

Strategic traffic flow management (as opposed to tactical traffic flow management)

refers to longer-term, 2-8 hour traffic management planning efforts at a larger scale,

perhaps regional or national rather than local.

13

We defined the “busiest airports” as those with the most passengers boarding at each

airport in 2015.

Page 9 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

In many cases, achieving the desired NextGen outcomes depends on the

successful implementation of multiple programs or capabilities. For

example, more efficient air traffic control routes may provide limited

benefits if air traffic controllers do not have access to tools to better

manage airborne traffic. To help manage the implementation of NextGen

improvements across programs, FAA has organized the operational

improvements—specific operational changes to the NAS, such as the

implementation of improved air traffic control procedures—into portfolios.

This portfolio-based approach views NextGen as an integrated effort

rather than a series of independent programs. See table 1 below for a list

and description of FAA’s 11 implementation portfolios.

Table 1: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)’s Portfolios of Next Generation Air

Transportation System (NextGen) Operational Improvements

Portfolio

Description

Improved Surface

Operations

Seeks to improve safety, efficiency, and flexibility on the

airport surface—on the ground at airports—by

implementing new traffic management capabilities for

pilots and controllers using shared surface movement

data.

Improved Approaches and

Low-Visibility Operations

Includes capabilities designed to increase airport access

and flexibility through procedural changes, improved

aircraft capabilities, and improved precision approach

guidance—navigation guidance given to pilots to guide an

aircraft on its descent to a runway.

Improved Multiple Runway

Operations

Seeks to improve access to closely spaced parallel

runways to enable more arrival and departure operations.

Performance-Based

Navigation

Uses navigation technologies to improve access and

flexibility in the National Airspace System (NAS) and

provide more efficient aircraft routes.

Time-Based Flow

Management

Enhances NAS efficiency by using the capabilities of the

Traffic Management Advisor decision support tool, which

assigns times when aircraft destined for the same airport

should cross certain points in order to reach the

destination airport at a specific time and in an efficient

order. Uses time instead of distance to help controllers

sequence aircraft.

Collaborative Air Traffic

Management

Coordinates decision making by flight planners and FAA

traffic managers to improve NAS efficiency, provide

greater flexibility to flight planners, and make the best use

of available airspace and airport capacity.

Separation Management

Provides air traffic controllers with tools and procedures to

separate aircraft. Safely reducing separation between

aircraft through the capabilities in this portfolio may

improve capacity, efficiency, and safety in the NAS.

Page 10 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

Portfolio

Description

On-Demand NAS

Information

Provides flight planners, air traffic controllers, traffic

managers, and flight crews with consistent and complete

information related to changes in various areas of the

NAS, such as temporary flight restrictions, equipment

outages, and runway closures.

Environment and Energy

Seeks to mitigate air quality, climate, energy, noise, and

water quality concerns from aviation through improved

scientific knowledge and integrated modeling; air traffic

modernization and operational improvements; new aircraft

technology; sustainable alternative aviation fuels; and

policies, environmental standards, and market-based

measures.

System Safety

Management

Uses data acquisition, storage, analysis, and modeling

capabilities being developed to ensure that new

capabilities either improve or maintain current safety levels

while simultaneously improving capacity and efficiency in

the NAS.

NAS Infrastructure

Provides research, development, and analysis of

capabilities that depend on and affect activities in more

than one NextGen portfolio.

Source: GAO review of GAO and Federal Aviation Administration documents. | GAO-17-450

In 2008, many of the aviation stakeholders we interviewed told us that

while they felt they were provided the opportunity to participate in

NextGen’s planning, many were not satisfied with the impact or outcome

of their participation. Some of these stakeholders expressed concern that

their input was not included in the development of planning documents

and other products, and that issues were not addressed or incorporated

in NextGen plans.

14

This participation is critical to NextGen’s

14

GAO, Next Generation Air Transportation System: Status of Systems Acquisition and

the Transition to the Next Generation Air Transportation System, GAO-08-1078

(Washington, D.C.: September 11, 2008).

Limited Stakeholder

Inclusion and

Communications Affected

Early Implementation, But

FAA Has Taken Steps to

Address These

Challenges

Evolution of Stakeholder

Inclusion

Page 11 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

implementation because NextGen depends heavily on airlines’ and other

stakeholders’ investments in NextGen technology and training.

The need for stakeholder buy-in and investment led FAA in 2009 to

request RTCA to form a task force of government and industry

stakeholders.

15

This task force —called the NextGen Mid-Term

Implementation Task Force—was asked to recommend NextGen

improvements that could be implemented with existing technologies in the

“midterm,” which was defined as lasting through 2018. In 2009, this task

force issued its recommendations to FAA; they prioritized operational

capabilities in six areas: surface, runway access, metroplex, cruise,

access to the NAS, and cross-cutting—recommendations that cut across

the previous five areas (see table 2).

16

FAA accepted the Task Force

recommendations and incorporated them into its annual NextGen

implementation plans.

Table 2: NextGen Mid-Term Implementation Task Force Recommendation Areas

Recommendation

Area

Description

Surface

Improving surface traffic management—the management of

traffic on the ground at airports—to reduce delays and enhance

safety, efficiency, and situational awareness through capture

and dissemination of surface operations data to pilots,

controllers, user operations centers, and other destinations.

Runway Access

Increasing runway access, especially in low visibility, to

converging, intersecting, and closely-spaced parallel runways

by leveraging potential capacity gains from accurate and

predictable flight paths, as well as enhanced surveillance

methods.

Metroplex

Relieving congestion and delays at major metropolitan areas’

airports, ine

ffi

ciencies at satellite airports, and surrounding

airspace by instituting FAA and industry teams that focus on

quality of implementation at each location and minimizing

conflicts between the operations of adjacent airports.

15

RTCA (formerly called the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics) is a public-

private partnership that provides a forum for developing consensus among competing

interests on aviation modernization issues, including providing industry recommendations

for FAA.

16

Surface refers to operations on the ground at airports. Cruise operations occur between

the climb and descent phases of flight. A metroplex is a geographic area covering several

airports that serve major metropolitan areas.

Page 12 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

Recommendation

Area

Description

Cruise

Improving efficiency of cruise operations—operations that

occur between the climb and descent phases of flight—by

increasing the ability to disseminate real-time airspace status

and schedules; improving flow management to better utilize

time-based metering—delivering aircraft to a specific place at a

specific time—and flight operator capabilities; and

implementing data communications between air traffic control

systems and aircraft to more e

ff

ectively manage tra

ffi

c and

exchange routing and clearance information.

Access to the National

Airspace System

Improving access to and services provided at airports other

than the Operational Evolution Partnership airports—the 35

U.S. airports with the most significant commercial activity—and

to low altitude, non-radar airspace by implementing more

precision-based approaches and departures, along with the

expansion of surveillance services to areas not currently under

radar surveillance.

Cross-Cutting

Recommendations that cut across the previous five areas,

including using data communications to enable more efficient

use of capacity in the National Airspace System, increasing the

ability to adapt to changing conditions through improved

dissemination of reroutes around weather and congestion,

creating a system for managing air traffic that leverages new

technologies and collaboration with the users, and

implementing integrated solutions to tra

ffi

c flow problems.

Source: GAO analysis of GAO, RTCA, and FAA documents. | GAO-17-450

In response to the task force recommendations, FAA has focused its

operational improvement efforts on key airports and metropolitan areas.

Specifically, through the Optimization of Airspace and Procedures in the

Metroplex (Metroplex) initiative, which began in fiscal year 2010, FAA has

focused on airspace redesign and deploying PBN procedures—

procedures that primarily use satellite-based navigation and equipment

on aircraft to navigate with greater precision—in metroplexes. These

metroplexes have a large effect on the overall efficiency of the NAS,

because congestion or delays at one metroplex can affect NAS

operations in other parts of the country. These metroplexes are shown in

figure 2.

Page 13 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

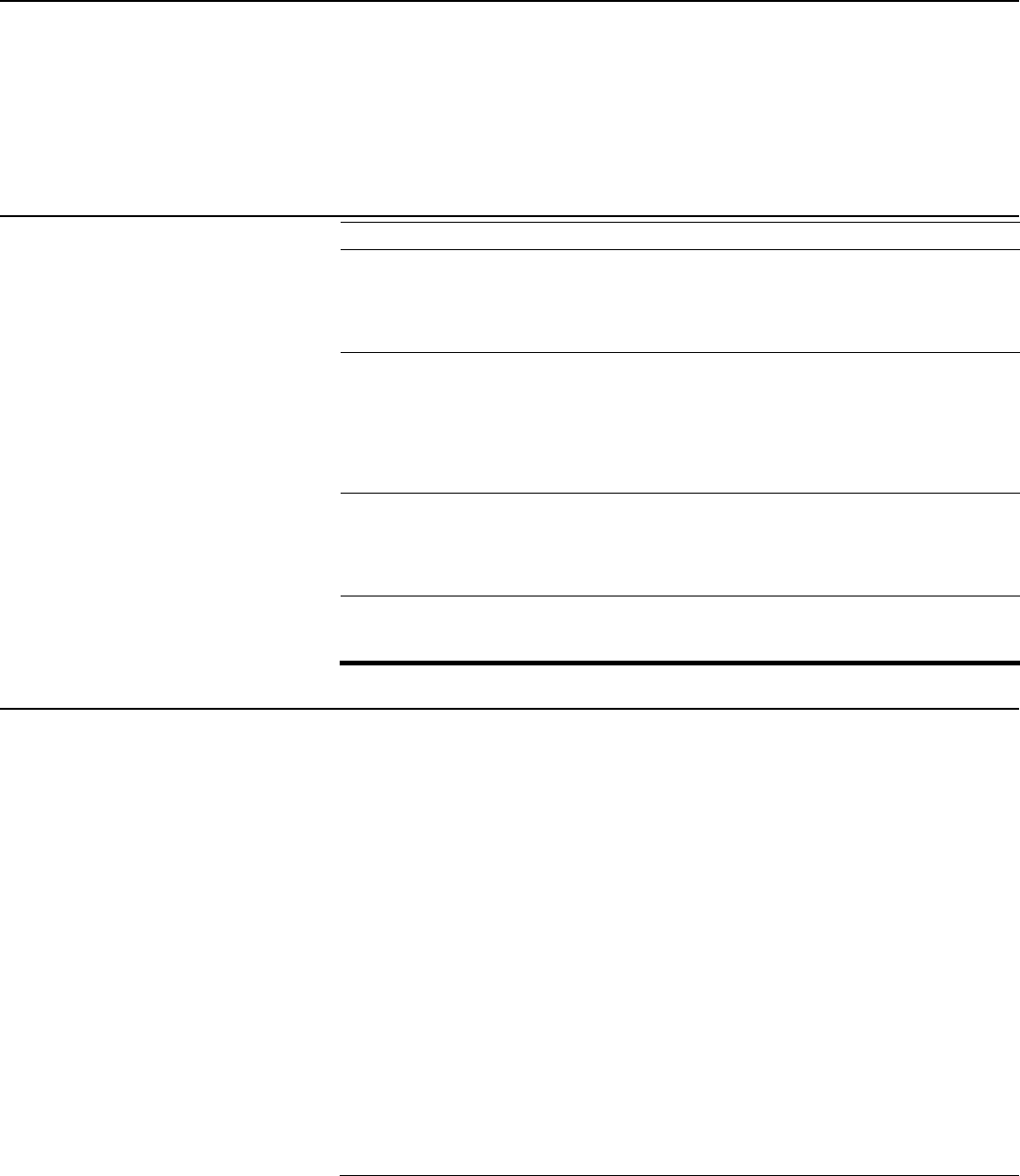

Figure 2: Metroplex Sites and Their Completion Status, as of March 2017

a

The Core 30 airports are a set of airports in major metropolitan areas with the highest volume of

traffic.

b

FAA’s Optimization of Airspace and Procedures in the Metroplex (Metroplex) initiative focuses on

airspace redesign and deployment of performance-based navigation procedures in metroplexes—

Page 14 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

geographic areas covering several airports that serve major metropolitan areas. These procedures

primarily use satellite-based navigation and equipment on aircraft to navigate with greater precision.

c

FAA “paused” work on the Phoenix metroplex in October 2015 due to legal action brought by the City

of Phoenix, and does not yet have plans to resume it.

In fiscal year 2013, FAA planned to complete projects at 10 metroplexes

by fiscal year 2016, but as of March 2017 FAA had completed projects at

only 4 metroplexes.

17

FAA considers a metroplex “completed” when,

among other things, it deploys new PBN procedures and when all air

traffic controllers are trained on the new procedures. According to FAA,

several factors caused the delay. FAA decided to implement ERAM

before addressing metroplexes because ERAM is required for some

NextGen operations. As a result, some Metroplex projects were delayed

until ERAM was implemented.

18

For example, the Charlotte and Atlanta

metroplexes were delayed from April 2014 until August 2015 while the

Atlanta Air Route Traffic Control Center implemented ERAM. In addition,

FAA changed the Metroplex program in 2015 to include enhanced

community involvement and outreach activities in Metroplex projects. This

change further contributed to delays. For example, according to FAA, the

introduction of the community involvement initiative caused a 15 month

delay in the Cleveland/Detroit Metroplex project. Under FAA’s current

community involvement strategy, a new Metroplex project would take

about 7 months longer to complete because of community involvement

activities. Further, according to FAA, sequestration and the 2013

government shutdown caused some delays due to employee furloughs

and travel restrictions. In addition to the 4 completed projects, 8 other

Metroplex projects are in various stages. While FAA plans to complete

the current set of 12 Metroplex projects by fiscal year 2019, FAA “paused”

work at one metroplex—Phoenix—in October 2015, due to legal action

brought by the City of Phoenix over noise created by new PBN

procedures. As of March 2017, FAA did not have plans to resume that

work.

17

FAA originally planned to complete 21 Metroplex projects by the end of fiscal year 2016,

but following a 2011 schedule review determined that neither it nor the aviation community

would have the personnel to stay on that schedule. In response, FAA reduced the number

of metroplexes and combined some of them into a list of 13 Metroplex locations. FAA later

deferred three of those locations (Boston, Chicago, and Memphis) and added two

locations (Denver and Las Vegas), resulting in the current list of 12 active metroplexes.

18

In 2012, we reported that insufficient stakeholder involvement and underestimates of the

complexity of software development had led to delays in ERAM and an estimated cost

increase of about $330 million. GAO-12-223. FAA attributed another delay in ERAM’s

completion (from August 2014 to March 2015) to the impact of sequestration.

Page 15 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

At completed metroplexes, not all aircraft are flying PBN procedures.

Although PBN procedures generally provide more efficient flight routes,

controllers may continue to route air traffic on conventional routes for a

number of reasons. For example, some aircraft may not have the proper

equipment to use the new procedure. Further, some airline officials we

interviewed reported receiving fewer benefits than expected from FAA’s

implementation of PBN. For example, officials at one airline told us that,

at one metroplex, FAA’s changes have led to that airline’s flying a less

efficient route into one airport, a route that requires its aircraft to use more

fuel and time to land at that airport.

Some stakeholders have called on FAA to include New York in its

Metroplex plans, due to its congestion and impact—such as flight

delays—on the rest of the NAS, as we have previously reported.

19

In

2013, we reported that FAA chose to exclude the New York/Philadelphia

metroplex because FAA did not want to initiate a new environmental

review process. FAA told us in 2017 that the agency plans to focus on the

northeast in the future, but does not have a current plan to implement

Metroplex improvements there.

At FAA’s request, RTCA established the NAC to provide advice on

NextGen implementation issues.

20

FAA designated the NAC to develop

aviation stakeholder priorities for NextGen implementation. These

priorities included both the national implementation of NextGen as well as

specific locations (such as airports) for NextGen improvements. In 2012,

the Integrated Capabilities Work Group of the NAC developed priority

operational improvements for major airports and metroplexes in the

midterm.

21

These priority improvements included capabilities such as

deploying PBN procedures that allow aircraft to take a more direct route

into and out of airports, which FAA expects will save both time and fuel.

19

GAO, NextGen Air Transportation System: FAA Has Made Some Progress in Mid-Term

Implementation, but Ongoing Challenges Limit Expected Benefits, GAO-13-264

(Washington, D.C.: April 8, 2013).

20

The NAC is comprised of a cross-section of senior executives from airlines, airports,

general aviation, and manufacturers, with the support of aviation stakeholders from the

federal government and international organizations. NAC members also include

representatives from pilot and air traffic controller unions.

21

The NAC includes a Subcommittee comprised of members with broad knowledge and

expertise related to NextGen. The NAC establishes working groups to accomplish

specific tasks.

Page 16 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

In 2014, FAA and the NAC issued a Joint Implementation Plan in which

FAA and industry described a set of activities that FAA and the aviation

community were committed to accomplishing within the next 3 years.

These activities covered four focus areas: data communications, multiple

runway operations, PBN, and surface operations and data sharing.

According to FAA, by the end of 2016, FAA had implemented 124 of 128

NextGen commitments it made for 2014 through 2016. For example, FAA

had deployed the System Wide Information Management (SWIM) Surface

Visualization Tool at five terminal radar-approach control facilities. This

tool provides air traffic controllers—who are not located in the airport

tower—with a real-time picture of airport surface traffic.

22

FAA and the

NAC have agreed to update the Joint Implementation plan annually and

develop rolling plans every 2 years to re-examine the needs of the NAS

and its users and to add milestones. FAA had an additional 57

commitments for 2017 through 2019 as of the beginning of 2017, and

industry had an additional 17 commitments for the same time period. In

addition to these commitments, in February 2017, the NAC voted to make

the Northeast Corridor – which stretches from Washington, D.C to

Boston, MA and includes the New York area – the fifth area of NAC

focus.

Concurrent with the work and recommendations of the RTCA’s Mid-Term

Implementation Task Force and the NAC, the DOT OIG and we

conducted reviews of NextGen. As a result of those reviews, from fiscal

year 2008 through fiscal year 2016 the DOT OIG and we issued 137 and

47 recommendations, respectively, aimed at improving the

implementation of NextGen. Our analysis shows that FAA has

implemented most of the recommendations related to NextGen programs

from us and DOT OIG since fiscal year 2008. More specifically, FAA has

implemented 39 of our 47 recommendations (83 percent), 6

recommendations are in process (13 percent), and 2 remain open (4

percent).

23

Additionally, DOT OIG has closed as implemented 103 of its

137 recommendations (75 percent) that we determined to be related to

22

SWIM enables sharing of air traffic management-related information among diverse

systems, and offers a single point of access for aviation data.

23

Recommendations that are in process are those for which FAA has submitted

information to close the recommendation, but either the information has not been fully

reviewed, or we determined it does not yet sufficiently address our recommendation.

Page 17 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

NextGen.

24

See appendix IV for an overview of the status of

recommendations DOT OIG and we made related to NextGen.

FAA has faced challenges in consistently communicating the status of

NextGen’s implementation. In 2010, we found that while FAA had broad

goals for NextGen, such as increasing capacity and reducing noise and

emissions, it had not developed specific goals and outcome-based

performance metrics to track the impact of and benefits realized from the

entire NextGen endeavor.

25

At that time, we recommended that FAA

develop an action plan to agree with stakeholders on a list of specific

goals and outcome-based performance metrics for NextGen. FAA

developed a set of performance metrics, which were used as a starting

point with industry collaboration, and aligned them with NextGen and

agency-wide goals.

Additionally, FAA launched the NextGen Performance Snapshots (NPS)

website to compare key NextGen initiatives with performance outcomes

at locations where NextGen technologies have been deployed. For

example, with some NextGen initiatives already deployed, FAA tracks the

measures and reports on airport performance at the Core 30 airports—a

set of airports in major metropolitan areas with the highest volume of

traffic–where NextGen technologies have been implemented. The agency

plans to continue to update the NPS with additional metrics as they

mature. Further, the NAC created a Joint Analysis Team which has

developed outcome measures for deploying certain NextGen capabilities.

For example, the team has measured the effect of efforts to update

standards for separation between and among aircraft on the efficiency of

operations at airports in Charlotte, Chicago, Indianapolis, and

Philadelphia. The objective of this capability is to decrease the separation

between and among aircraft and thereby allow more takeoffs and

landings and greater efficiency and capacity for airports. FAA officials told

us that FAA continues to work with industry partners to ensure that FAA is

validating and verifying implementation progress of NextGen technology

and reporting successes and beneficial effects. However, some

stakeholders told us that FAA continues to focus on outputs, such as the

24

DOT OIG closes a recommendation after the Department of Transportation has agreed

with the recommendation, has taken appropriate corrective action, and has provided DOT

OIG with sufficient supporting evidence to demonstrate that the action was taken.

25

GAO, NextGen Air Transportation System: FAA’s Metrics Can Be Used to Report on

Status of Individual Programs, but Not of Overall NextGen Implementation or Outcomes,

GAO-10-629 (July 27, 2010).

Measuring and Reporting

Implementation Status

Page 18 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

number of ADS-B ground stations deployed, instead of outcomes, such

as improvements in safety, capacity, or efficiency.

According to FAA officials, current segments of NextGen programs are

generally on schedule, and FAA documents indicate that FAA plans to

implement the concepts that will complete the transformation of the NAS

to a NextGen system by 2025.

26

According to FAA, these timeframes are

updated at least annually. FAA also has an Integrated Master Schedule

for key NextGen activities; this schedule is updated at least every 3

months. In describing these concepts, FAA does not state that NextGen

will be implemented or completed by 2025. Rather, FAA describes

several interim milestones that are scheduled to occur between now and

2025. Taken together, the completion of these milestones—such as

deploying Data Communications and expanded PBN—will result in the

implementation of NextGen concepts, according to FAA. According to

MITRE Corporation, the aviation industry has been able to leverage

current ground-based and aircraft-based navigation capabilities to realize

initial benefits of NextGen at key metroplex areas.

27

For more information

on the current status of implementation of select NextGen programs and

future implementation plans, see Appendix III. After 2025, FAA plans to

26

These concepts are described in FAA, The Future of the NAS (2016), FAA’s update to

its NextGen Mid-term Concept of Operations planning document issued in 2011. We did

not validate FAA’s implementation schedule and are not predicting whether FAA will meet

these milestones.

27

MITRE Corporation is a not-for-profit corporation that operates federally funded research

and development centers. MITRE’s Center for Advanced Aviation System Development

works with FAA to develop NextGen.

FAA Plans to Complete

the Majority of Planned

NextGen Implementation

by 2025 and within Earlier

Cost Estimates

FAA Plans to Implement Most

NextGe

n Concepts by 2025,

b

ut Has Deferred Some

Activities Until after 2030

Page 19 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

continue enhancing technology and implementing advanced NextGen

applications as part of its ongoing efforts to improve the NAS.

28

In August 2017, FAA estimated that NextGen had delivered $2.7 billion in

benefits through 2016. According to FAA, these benefits were realized by

airlines, the FAA, and the general public, and included benefits derived

from fuel savings, reductions in crew and maintenance costs, additional

airline flights, FAA efficiencies, safety improvements, passenger time

savings, and reductions in carbon dioxide emissions.

In addition, FAA and industry team and the MITRE Corporation have

conducted studies to determine the benefits from the NextGen

improvements FAA has already deployed. For example, a November

2015 MITRE Corporation analysis found that Metroplex procedural

improvements resulted in fuel savings at one metroplex, although less

than anticipated. Specifically, the analysis of the impact of new Metroplex

procedures in the Houston Metroplex projected an annual benefit of $5.3

million in fuel savings to operators at two airports in Houston; however,

the analysis also noted that these benefits were lower than the predicted

savings of $8.3 million annually.

29

Similarly, June 2016 and February

2017 assessments of the effect of revised wake separation standards by

the Joint Analysis Team showed positive results. These standards specify

the required distance between aircraft due to the turbulence created by

the air behind aircraft. The Joint Analysis Team’s assessments found cost

savings at four of five airports.

30

Specifically, the studies found savings for

flights on congested runways, and airports could increase the frequency

of takeoffs and landings.

31

The studies found a decrease in separation for

arrivals at all five locations, and a decrease in separation for departures

at four of the five locations, leading to increased capacity and projected

cost savings of over $4.3 million annually. However, the studies also

28

FAA officials pointed out that the aviation industry will not be able to use some of the

more advanced capabilities that these programs are expected to provide until aircraft are

equipped to use these capabilities.

29

The MITRE Corporation, Houston Metroplex Post-Implementation Analysis (McLean,

Virginia: November 2015).

30

The performance assessment included separation data for five airports: Charlotte

Douglass International Airport; O’Hare International Airport; Chicago Midway International

Airport; Indianapolis International Airport; and Philadelphia International Airport.

31

RTCA, Joint Analysis Team: Performance Assessment of Wake ReCat (June 2016);

RTCA, Joint Analysis Team: Performance Assessment of Wake ReCat in Indianapolis and

Philadelphia and Fuel Analysis for North Texas Metroplex (February 2017).

Page 20 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

found that the effects at individual airports would depend on the type and

number of aircraft at each airport.

According to FAA, some airlines and shipping companies have also

reported benefits from revised wake-separation standards. FAA reports

that Delta Air Lines estimated that revised separation standards at Atlanta

increased Delta’s average daily operations by 6.8 percent, among other

benefits, resulting in $13.9 to $18.7 million in annual savings. Similarly,

FAA reports that United Parcel Service, Inc. estimated 1.5-million gallons

in annual fuel savings from revised standards at Louisville, and FedEx

Corporation estimated 4.1-million gallons in fuel savings from revised

standards in Memphis.

While some cost savings have already occurred, not all NextGen

activities are being implemented. According to FAA officials, they have

identified six NextGen activities that FAA had previously planned to

complete by 2025, but has now deferred until after 2030 due to technical

or operational infeasibility or changed operational needs. FAA officials

explained that these applications are not in progress, and may be

continually deferred, redefined, or never implemented. For example, in

2011 FAA planned to implement automated conflict-resolution aids—a

mechanism to enable air traffic controllers to manage more aircraft while

maintaining safety—by 2018. However, FAA’s revised plan for NextGen

has deferred implementation of these applications until after 2030.

According to FAA, FAA deferred them for reasons such as costs

outweighing prospective benefits, a lack of sufficient air traffic to justify

implementation, or deployment of other capabilities that provide similar

benefits. See appendix V for more information about these deferred

programs.

FAA’s current total cost estimate for implementing NextGen through 2030

is within the JPDO’s 2007 estimates. In 2007, JPDO projected that

through fiscal year 2025, FAA’s total NextGen cost would be between $15

billion and $22 billion and that costs to the aviation industry would be

between $14 billion and $20 billion. In 2016, FAA estimated the agency’s

cost through fiscal year 2030 at $20.6 billion—within the range of JPDO’s

2007 estimate of $15 to $22 billion.

32

FAA also estimated $15.1 billion in

32

According to FAA officials, FAA business case estimates are intended for the purpose of

cost-benefit analyses and therefore estimate costs in years beyond FAA budgetary

planning. These estimates include capital expenditures, research and operations, but do

not include the cost of FAA staff and training.

The Current Cost Estimate for

NextGen is Within Earlier

Estimates, But NextGen Has

Changed Over Time

Page 21 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

costs for the aviation industry—also within the range of the 2007

estimate. Of the $20.6 billion in estimated costs, FAA indicated that the

agency had already expended $5.8 billion through fiscal year 2014—

approximately 28 percent of the estimated cost of NextGen—and

projected NextGen costs of $14.8 billion from fiscal year 2015 to 2030.

Assessing prior NextGen cost estimates against current estimates is

difficult because the NextGen program has changed since 2007. As

previously discussed, six NextGen activities were removed for reasons

such as costs outweighing benefits or insufficient air traffic to justify

implementation (see appendix V). Other programs, such as PBN, were

added to the NextGen program after 2007. As a result, FAA officials

stated that it is somewhat coincidental that the 2016 estimate is within the

range of the 2007 estimate.

We recently found that NextGen cost estimates have evolved, but not

increased markedly since 2004.

33

According to FAA, NextGen cost

estimates have changed in part because earlier estimates considered the

cost of upgrades and enhancements, but over time estimates have also

considered the cost of sustaining systems, PBN procedures, and recently,

the costs associated with integrating unmanned aircraft systems (UAS)

(commonly known as “drones”) into the NAS.

34

FAA officials explained

that FAA’s current estimated total cost for the aviation industry to equip

for NextGen-capable avionics—electronic equipment found in modern

aircraft—is lower than earlier estimates in part because smaller aircraft

are being replaced by new, larger, and better equipped aircraft, reducing

the number of aircraft in the commercial fleet. According to MITRE

representatives, several factors have contributed to the lower aviation

industry’s cost estimates, including changes in assumptions for the

expected volume of commercial traffic, modifications to the cost of

equipage, and reduction in uncertainty about what equipment aircraft

would need.

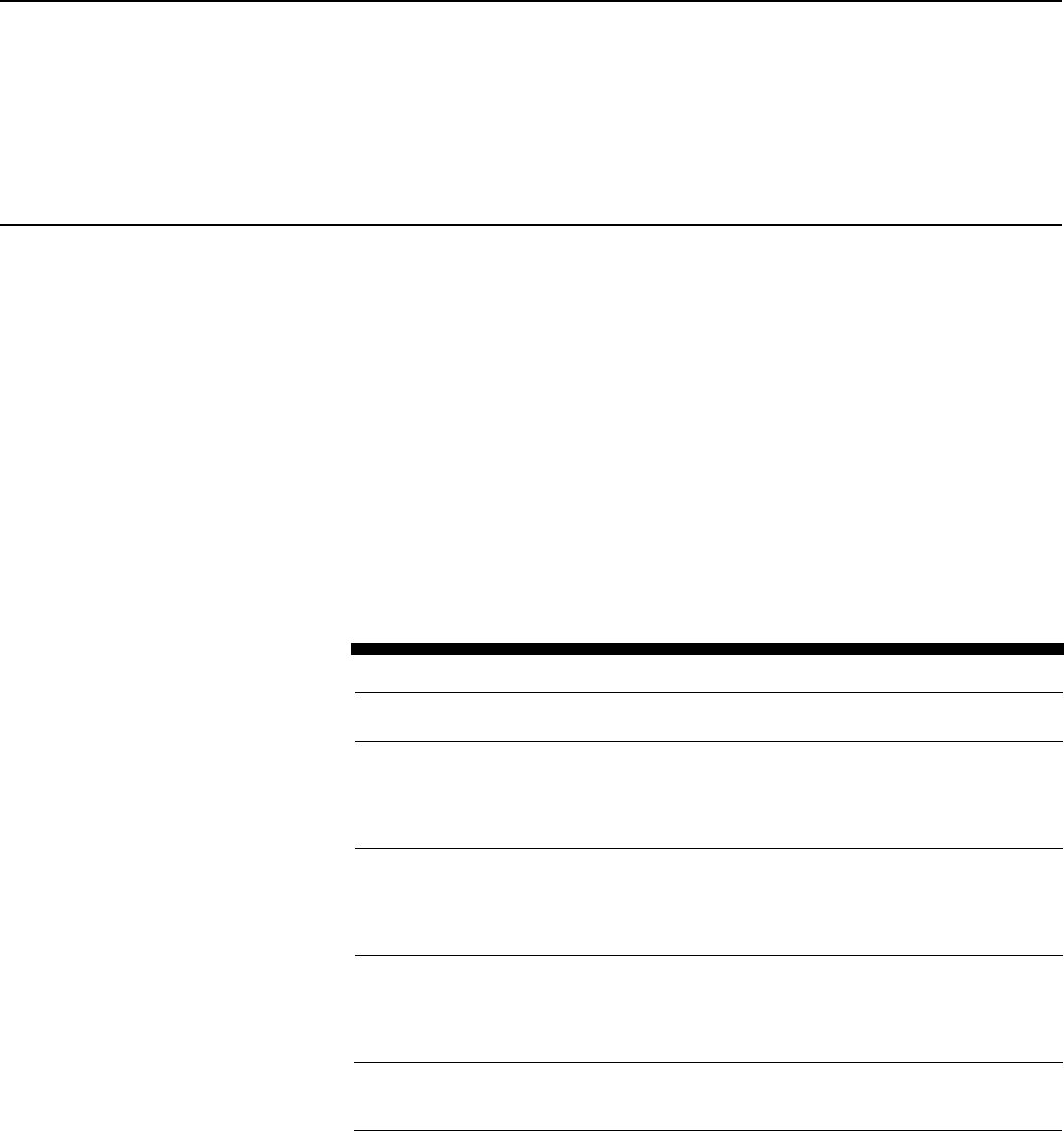

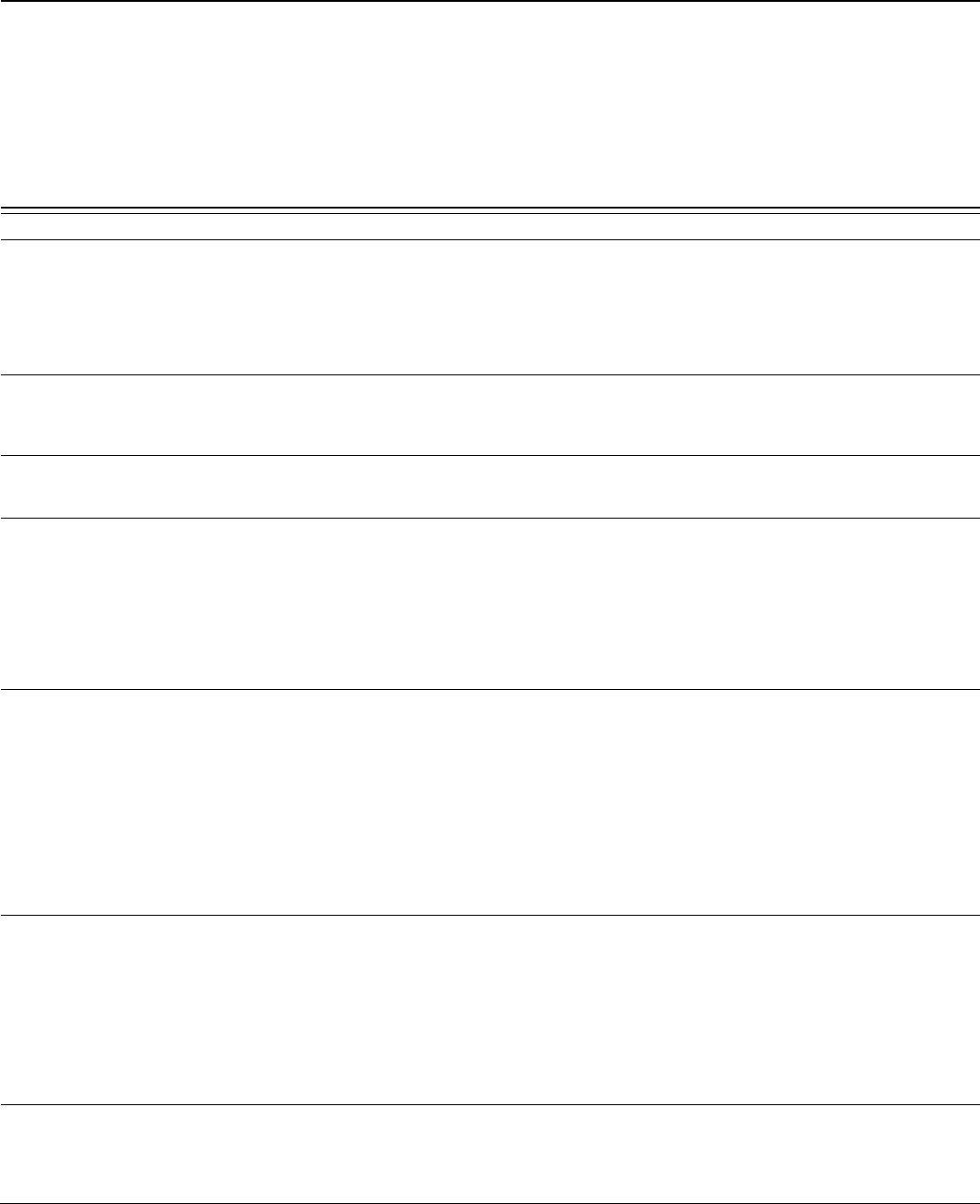

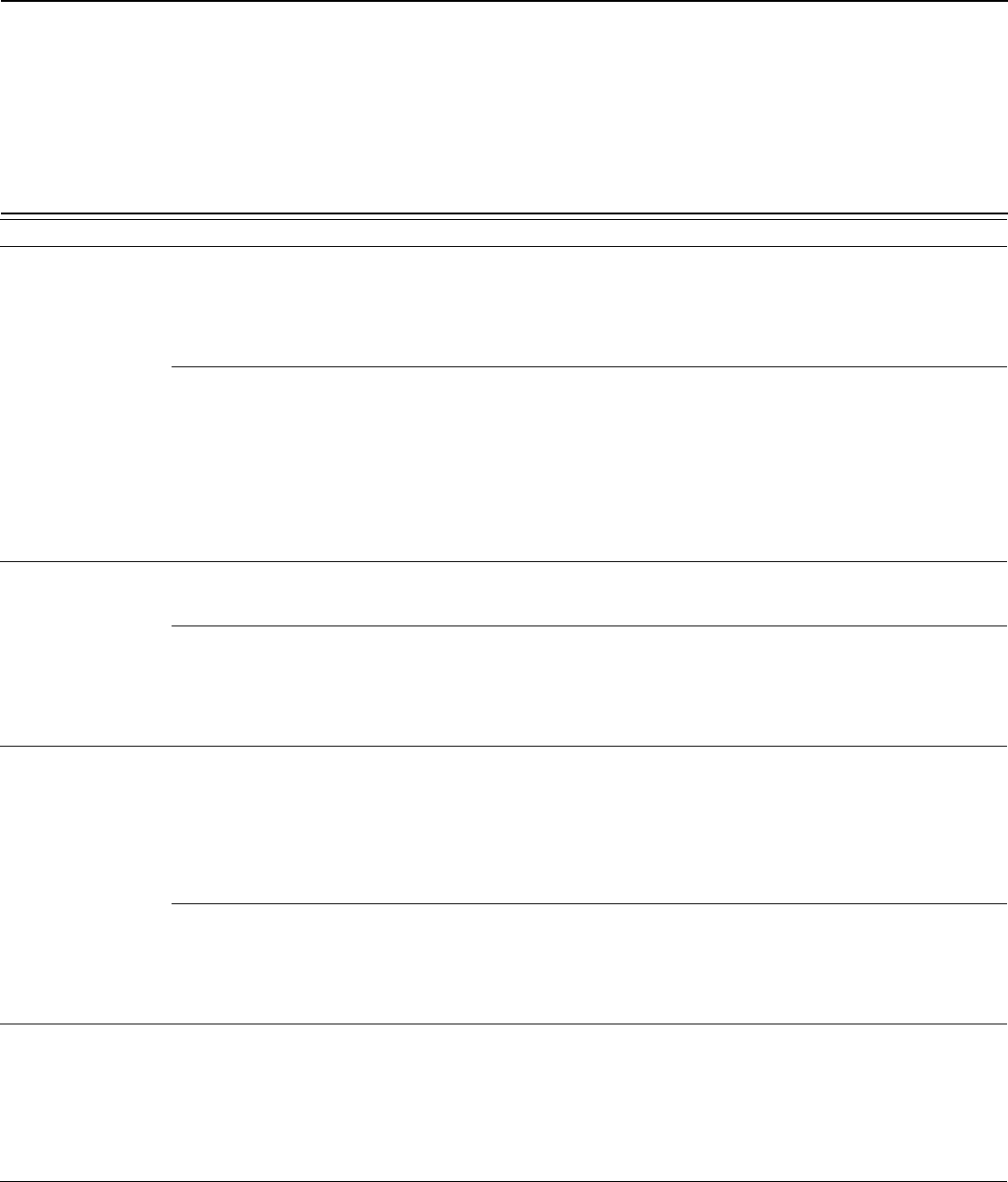

Based on an analysis of FAA budget documents and data, we recently

found that FAA received approximately $7.4 billion for NextGen from

33

GAO, Next Generation Air Transportation System: Information on Expenditures,

Schedule, and Cost Estimates, Fiscal Years 2004-2030, GAO-17-241R (Washington,

D.C.: November 17, 2016).

34

FAA established a Drone Advisory Committee in 2016 to, among other things,

recommend options for how to fund activities required to integrate drones into the NAS.

Page 22 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

fiscal year 2004 through fiscal year 2016.

35

According to FAA officials,

operational costs of fully implemented NextGen programs are not

included in these funds. Congress appropriates most of the funding to

FAA from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund,

36

which receives revenues

from a series of excise taxes on airline tickets, aviation fuel, and cargo

shipments paid by users of the national airspace system.

37

See figure 3

for an overview of federal funds FAA has received for NextGen programs

and activities.

Figure 3: Federal Funds the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Has Received for Next Generation Air Transportation

System (NextGen) Programs and Activities, Fiscal Years 2007 through 2016

Notes: Dollar amounts presented in the figure are nominal values. From 2004 through 2006, FAA

distributed $25,978,000 of its research and development funds for JPDO to plan and coordinate the

transition to NextGen.

35

GAO-17-241R. According to FAA officials, there is considerable variation in the

obligation rates for facilities and equipment (F&E) projects due to the diverse nature of

their procurement cycles.

36

26 U.S.C. § 9502.

37

The remainder of FAA’s appropriations comes from the General Fund of the U.S.

Treasury. The Airport and Airway Trust Fund provides funding for FAA’s capital accounts,

including research, engineering and development (RE&D) and facilities and equipment

(F&E).

Page 23 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

a

According to FAA officials, the agency did not identify programs and activities as NextGen in its

budget documents until 2008, but officials were able to identify three NextGen-related programs for

which FAA received facilities and equipment funds for in fiscal year 2007, in addition to research and

development funds it distributed to the Joint Program Development Office (JPDO) for NextGen.

b

In 2013 FAA received $883,328,000 for NextGen, but FAA officials noted that they reprogrammed

$27,900 thousand from NextGen to other programs.

In addition to funds for NextGen, FAA has also invested in other

programs on which aspects of NextGen are dependent. For example,

according to FAA, the deployment of the core ERAM program cost $2.58

billion when completed in 2015, and FAA estimates that all completed

and current TAMR programs will cost $3.082 billion.

38

FAA faces several remaining challenges as it continues to implement

NextGen, such as uncertainties regarding future funding, leadership

stability, aircraft equipage, and cybersecurity issues. FAA is taking some

actions to address these challenges by, for example, prioritizing and

segmenting NextGen improvements into smaller pieces that each require

less funding. While it is not possible to eliminate all uncertainties, FAA is

adopting Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) as a tool to help it

anticipate and manage risks across NextGen programs, and plans to use

ERM to mitigate future risks.

Most of the aviation stakeholders we interviewed (22 of 34) told us that

uncertain funding has been a challenge and has affected FAA’s efforts to

implement NextGen.

39

FAA officials told us that sequestration and

38

ERAM’s original acquisition program start date was June 2003 and Terminal Automation

Modernization and Replacement’s start date was February 1996. The Terminal

Automation Modernization and Replacement program upgrades the computer system

used by air traffic controllers to provide air traffic control services in terminal airspace, the

airspace immediately surrounding major airports.

39

The numbers reported for our open-ended questions represent those stakeholders who

identified a challenge to consider or suggested a change. It does not mean that the

remaining stakeholders agreed or disagreed with that challenge or change.

FAA Faces Various

Challenges to

Implementing

NextGen

FAA is Taking Steps to

Address Challenges to

NextGen Implementation

Uncertain Funding

Page 24 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

“continuing resolutions” have had an impact on FAA’s ability to plan and

implement NextGen.

40

Uncertain funding includes not knowing the

amount of funding that will be appropriated to NextGen or when the

funding will become available. From fiscal year 2011 through fiscal year

2016, Congress has passed 25 continuing resolutions that impacted

funding for FAA, ranging from 1 day to 365 days, with an average of

approximately 46 days. In 2014, we reported that some stakeholders told

us that stops and starts associated with continuing resolutions make it

difficult for FAA to carry out long-term planning and strategic development

of future technologies.

41

We found that operating under continuing

resolutions can also complicate agency operations and cause

inefficiencies, such as leading to repetitive work, limiting agencies’

decision-making options, and making trade-offs more difficult.

42

Uncertain

funding was also cited by some stakeholders as a major reason for

Congress to consider restructuring the FAA, which is discussed later in

this report.

43

FAA has taken steps to mitigate challenges resulting from uncertain

funding. Specifically, it has prioritized NextGen improvements in

collaboration with the NAC and has segmented some NextGen programs

into smaller pieces that each requires less funding. In 2012, we found that

FAA broke large, complex programs, such as SWIM, into smaller

segments to reduce risk.

44

We previously found that this approach can

improve program management by positioning FAA to make any

40

A continuing resolution is an appropriations act that provides budget authority for federal

agencies, specific activities, or both to continue in operation when Congress and the

President have not completed action on the regular appropriations acts by the beginning

of the fiscal year.

41

GAO-14-770.

42

In September 2009 and March 2013, we also found that continuing resolutions can

create budget uncertainty for agencies about both when they will receive their final

appropriation and what level of funding will ultimately be available. GAO, Continuing

Resolutions: Uncertainty Limited Management Options and Increased Workload in

Selected Agencies, GAO-08-879 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 24, 2009); and GAO, Budget

Issues: Effects of Budget Uncertainty from Continuing Resolutions on Agency Operations,

GAO-13-464T (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 13, 2013).

43

H.R. 2800, the Aviation Funding Stability Act, was introduced in June 2017 and seeks to

provide more certain funding for aviation programs by taking the Airport and Airway Trust

Fund off budget and making all Trust Fund revenues and the Trust Fund’s uncommitted

cash balance available immediately.

44

GAO, Air Traffic Control: FAA’s Modernization Efforts Past, Present, and Future,

GAO-04-227T (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 30, 2003) and GAO-12-223.

Page 25 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

necessary corrections earlier in development, and thus help FAA avoid

costly late-stage changes. However, we also found that this approach can

increase the duration and possibly the total cost of the program.

45

For

example, in 2015 we found that FAA had divided capital investments for

Data Communications into small segments, raising questions from the

aviation industry about when FAA will fully implement Data

Communications.

46

A related funding challenge is the need for FAA to have funding sufficient

to support both existing legacy system maintenance and the

implementation of NextGen capabilities. As we reported in November

2015, according to FAA officials, NextGen implementation in future years

is dependent on the timing and amount of future appropriations.

47

Specifically, any funding delay in one NextGen program can lead to

increased costs for FAA, even if the delay does not result in a direct cost

increase to a program. These cost increases occur because FAA staff

must continue to manage program implementation and maintain any

legacy system that the program is replacing. In addition, NextGen

programs are interdependent, so a schedule delay in one program can

also affect how and when other programs will be implemented.

48

In

response to the challenge of maintaining the legacy system while also

implementing new systems and capabilities, FAA officials told us that

funding has been allocated to account for the “technical refresh” of

existing systems and other maintenance related issues, and that FAA will

continue to monitor and prioritize the delivery of NextGen capabilities

while maintaining existing systems.

49

According to FAA officials,

approximately 55 percent of FAA’s current budget is used to maintain the

current air traffic control system. The longer that legacy systems are

maintained, there is a greater likelihood that they will continue to require

increasingly large shares of the FAA budget and reduce the amount of

45

GAO-04-227T and GAO-12-223.

46

The Data Communications program aims to supplement existing voice communications

between pilots and air traffic controllers and serve as an enabler for the NextGen

operational improvements. GAO, Aviation Finance: Observations on the Effects of Budget

Uncertainty on FAA, GAO-16-198R (Washington, D.C.: November 19, 2015).

47

GAO-16-198R.

48

GAO-12-223.

49

The term technical refresh can refer to software and hardware enhancements, upgrades

or modernization of system components, replacements needed to address supportability

and maintainability issues, among other things.

Page 26 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

funds available to implement NextGen. In 2011, we concluded that FAA

will have to balance its priorities to ensure that NextGen implementation

stays on course while also maintaining the current infrastructure that is

needed to ensure the safety and reliability of the NAS.

50

NextGen program leadership has undergone significant changes that are

likely to continue. Specifically, while the FAA administrator is appointed to

a 5-year term, there have been four administrators since a previous

administrator’s term ended in September 2007, including no confirmed

administrator for all of 2008 and 2012. The Deputy Administrator-Chief

NextGen Officer left the position in June 2016 after 3 years in the

position, and a new Deputy Administrator was sworn in in June 2017.

Furthermore, since the position of Assistant Administrator for NextGen

was created, in late 2011, three assistant administrators and one interim

assistant administrator have filled the position. Additionally, a new

Secretary of Transportation was sworn in in January 2017, and the

current FAA administrator’s term expires in January 2018. We previously

found that programs benefit from having experienced program managers

who provide consistent leadership through major phases of a program.

51

Additionally, we found that leading practices of successful organizations

indicate that programs can be implemented most efficiently and

effectively when managers are empowered to make critical decisions and

can be held accountable for results.

52

Conversely, the absence of stable

and consistent leadership may have the opposite effect on project

implementation. For example, continued uncertainty about the FAA’s

leadership of NextGen could affect FAA’s ability to manage the various

efforts needed to achieve full implementation of NextGen. As we have

previously reported, industry stakeholders have expressed concerns

about the fragmentation of authority and lack of accountability for

NextGen, two other factors that could delay its implementation.

53

Legislation introduced in June 2017 would establish a separate not-for-

profit corporate entity outside of FAA to operate the nation’s ATC

50

GAO, Next Generation Air Transportation System: FAA Has Made Some Progress in

Implementation, but Delays Threaten to Impact Costs and Benefits, GAO-12-141T

(Washington, D.C.: October 5, 2011).

51

GAO, Defense Acquisition: Strong Leadership Is Key to Planning and Executing Stable

Weapon Programs, GAO-10-522 (Washington, D.C.: May 6, 2010).

52

GAO-13-264.

53

GAO-13-264.

FAA Leadership Stability

Potential ATC Restructuring

Page 27 GAO-17-450 Air Traffic Control Modernization

system.

54

This proposal could affect the implementation of NextGen. For

example, the change could result in more certain funding, as funding

would not be subject to the federal budget process. However, other

challenges could develop. In October 2016, we reported that subject area

experts, aviation stakeholders, and FAA officials identified issues that will

need to be considered if such a transition were to occur. Some of those

issues directly affect NextGen implementation. Specifically, stakeholders

told us that one issue would be the amount of time and costs required to

complete a transition from FAA to another ATC operator. This transition

time would include the time it could take to terminate or revise current

contracts between FAA and companies that produce NextGen

technologies. Another issue that stakeholders identified is how

management and workforce roles and responsibilities would be defined

within the new entity and FAA. For example, selected experts identified

the importance of clearly delineating each organization’s roles and

responsibilities to ensure a smooth transition.

55

According to FAA, the

transition could create some uncertainty among some employees over

future workforce or organizational changes. While it is uncertain how a

transition would affect NextGen implementation, the legislation includes a

requirement for FAA to prioritize and track progress on some NextGen

programs before the transition occurs.

To achieve desired benefits, NextGen requires system users such as

aircraft owners and operators to equip their aircraft with new avionics that